As a student with an invisible physical disability, I know ableism is ever-present in society. I’m used to dealing with intrusive questions about injuries, being banned from buildings, and being accused of faking physical issues. I’ve been dealing with these issues my whole life. I thought I already knew how bad ableism could be, but apparently I was wrong.

Two weeks into the new semester, I seriously injured my right knee. As someone who is prone to injury, this incident was not a surprise, but it had a huge impact on my semester. For the first time in my life, I was on crutches and my physical condition was visibly revealed. The way I was treated by others during this time was completely foreign to me, so there must have been something going on. The many forms that ableism manifests itself in greatly impacts the way disabled people interact with the world.

First, a quick observation: Opening doors. While I was on crutches, people went out of their way to hold doors for me, which seems like the kind of thing any decent person would do for anyone else. But when I limped to class without my crutches after twisting my ankle or hurting my back, people would purposely close doors in my face, mocking me for pretending to be injured. Some people decided that because I had an injury that was not immediately obvious, I didn’t deserve the basic respect of holding a door for someone less than five feet away.

When I was visibly impaired, I felt uncomfortable with how much people around me tried to help me. Going out of my way to open a door for someone with an injury seems like a kind gesture, but it wasn’t always received that way. When I was injured, I couldn’t put on my shoes myself, but I was able to press the button for an automatic door, and later, when I could only use one crutch, I was able to open the door myself. When someone was waiting at the door and opened it for me when I was still 30 feet away, or even worse, ran in front of me to open the door, I often felt like they were taking away what little independence I had.

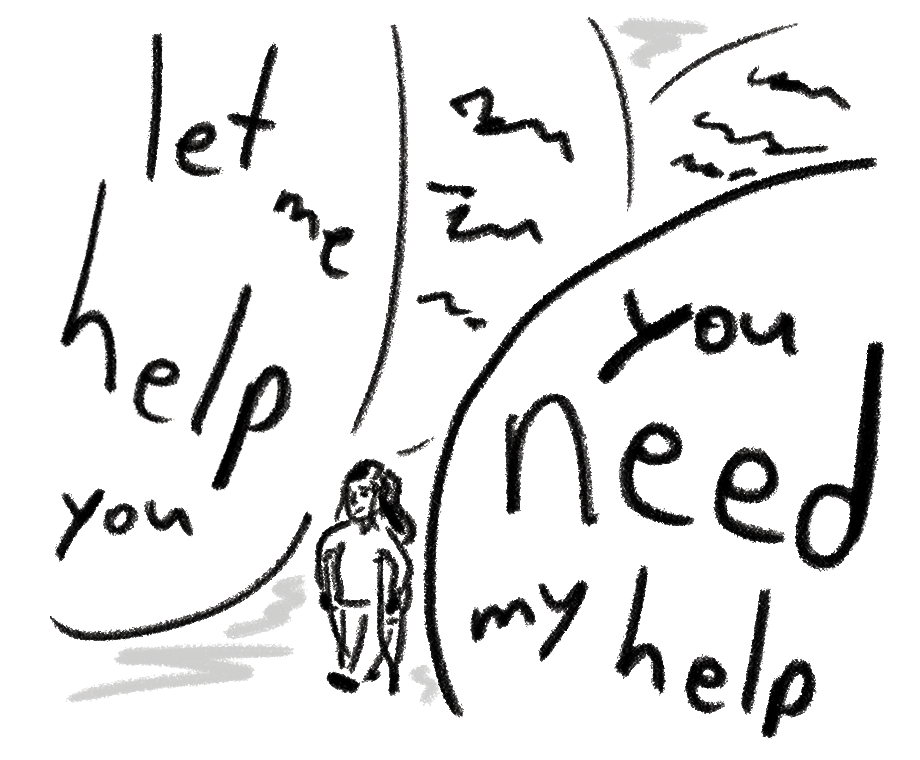

This is common in the disability community. Many disabled people tell stories of strangers deciding it’s OK to push someone’s wheelchair without permission. The wheelchair user may be completely independent, but that doesn’t matter. If someone decides to “help,” the disabled person can’t do anything. When we complain, we are often told, “Just let him help! You need it!” Too often, disabled people are seen as an outlet for able-bodied people’s sympathy. Others want to appear kind or do good things, but disabled people have no say in it.

If someone asks for help, it’s a different story. If I ask someone to open a door, I would hope that request would be respected, whether I was injured or not. But we shouldn’t assume that we need assistance. I know there are people who will open doors for us, but this is very different. I was simply walking across a room to a door and someone ran past me, nearly tripping me while trying to open the door. I had no intention of leaving, but the person assumed I needed them to open the door for me. They pretended to be upset that I didn’t sincerely thank them and take advantage of their “kindness.” Why should I thank someone so that I can feel like I’m doing a good thing when I nearly hurt myself even more? Why should I apologize for doing my job and not adjusting my course to accommodate someone else’s ego?

Society’s perception is that all disabled people are helpless and incapable, unable to exist in this world without endless support, but even when disabled people are independent, others are reluctant to leave them alone. Applying basic accommodations allows many disabled people to live fulfilling lives and participate in society. However, when disabled people find ways to get through the world without relying on others, such as using a service dog, they often face further discrimination. In the case of service animals, whether they are guide dogs for the blind or medical alert dogs for heart disease, they are often not welcome in businesses. Although it is illegal to ban service animals from establishments in the United States, people still try to do so. Harassment can also come not only from business owners, but from other customers who find someone’s accommodations annoying. When disabled people do not have to rely on others, they are forced to endure further harassment from the people around them.

Ableism has always been present throughout society, which means that ideas and stereotypes are often imposed on this minority. One of the biggest examples of this impact can be seen in labels. You may have noticed that I have used the term “disabled” throughout this article, and this is intentional. It is a surprisingly controversial statement, mainly because able-bodied people are trying to impose another label on individuals who do not want one. If someone wants to use these terms as part of their identity, that is their freedom, but problems arise when certain terms are stigmatized against the will of people who identify themselves with them.

The reason why the new terminology has not been widely adopted by many disabled people is the ambiguity of what it actually means and the intention behind its use. The terms “differently abled” and “special needs” can imply that the person has abilities or skills that the general population does not have. In conversation, these terms have become a way to make disability seem positive. These terms are often supported by able-bodied people, who often use these phrases to accuse disabled people of being “too hard on themselves” or “seeing things too negatively.” To make matters worse, the term “handicapped” is trying to do the same problematic thing to an originally problematic term. The term “handicap” is so deeply ingrained in society that many people, for example, refer to disabled parking as a “handicap spot,” but the origins of the term are incredibly ableist. The word comes from the phrase “hat in hand,” which means an unemployed person begging for money. This perpetuates the stereotype that disabled people cannot get a job, so they receive assistance and rely on able-bodied people to survive.

Some people argue that person-centered language is needed in this case, and insist on using “disabled” instead of “disabled.” The argument here is that it is more important to emphasize being a person than being disabled, and so it needs to be said that way. As with all the terms I have listed so far, this idea has been imposed on disabled people by able-bodied people. This is a personal experience shared by many disabled people, including me. More than once, I have been told to use more positive terms when talking about my disability, and this comment always came from able-bodied people. I have never heard other disabled people insist on using person-centered language. It is always able-bodied people who claim to be allies of disabled people. Insisting on the use of these terms is a form of cultural imperialism, an attempt to change our community to fit the majority perspective. But why should we listen to these pressures?

I am disabled. This is an integral part of my identity and should be treated as such. Why should someone get to dictate to me how I present myself? No one is arguing that LGBTQIA+ people should insist on being called “LGBTQIA+ people.” So why does it matter to the disability community? Because able-bodied people want to sympathize with us, and think that changing a “socially acceptable” term to one we don’t agree with somehow justifies their treatment of us.

Disabled people are smart, independent, capable individuals with goals and inspirations, not there to be pitied by others. Whether our disability is visible or not, we deserve the same respect as everyone else. If I had a problem, there are some basic points of respect I would like people to follow: If I ask for help, please help me. If I want to do something myself, please respect that. I have a voice and I can communicate if I need help. Regarding terminology, when deciding what terms to use for disabled people, please listen to disabled people, not ableism and cultural imperialism rhetoric.

The treatment of people with disabilities in society needs to change. There is no specific area where the problems are isolated. These issues are systemic and pervasively impact every area of life. Are there clear solutions? I’m not sure. But what I do know is that the disability community cannot be silent about these issues. Those affected need to be included in the conversation.