The governments of President Daniel Ortega and his wife, Vice President Rosario Murillo, have suppressed all forms of dissent and continued to isolate Nicaragua.

The government has strengthened its grip on power by cracking down on critics, including members of the Catholic Church, and dismantling civil space, shutting down media outlets, NGOs and universities on a large scale, violating freedom of expression and association, and restricting the right to an education.

Other persistent problems include a total ban on abortion, attacks on indigenous and African communities, and widespread impunity for human rights violations.

Persecution of critics

Nicaraguan human rights groups reported that as of October 81 suspected government critics remained in detention, most of them charged with “undermining national unity” and “spreading fake news.”

In February, the government revoked the citizenship of 317 people, including 222 political prisoners who had been deported to the United States, and confiscated their assets, labelling them “traitors,” a decision that violates international human rights law and has left many stateless.

Authorities removed the birth certificates and educational records of those expelled from the civil registry and disrupted their right to access personal information. They also removed the personal data of critics from the Nicaraguan Social Security Agency and stripped many of their pensions. In May, the Supreme Court permanently suspended the licenses of 25 lawyers and notaries, ruling that they were considered “foreigners” and therefore could not practice in Nicaragua.

Religious Freedom

Attacks on the Catholic Church that began in 2018 have intensified.

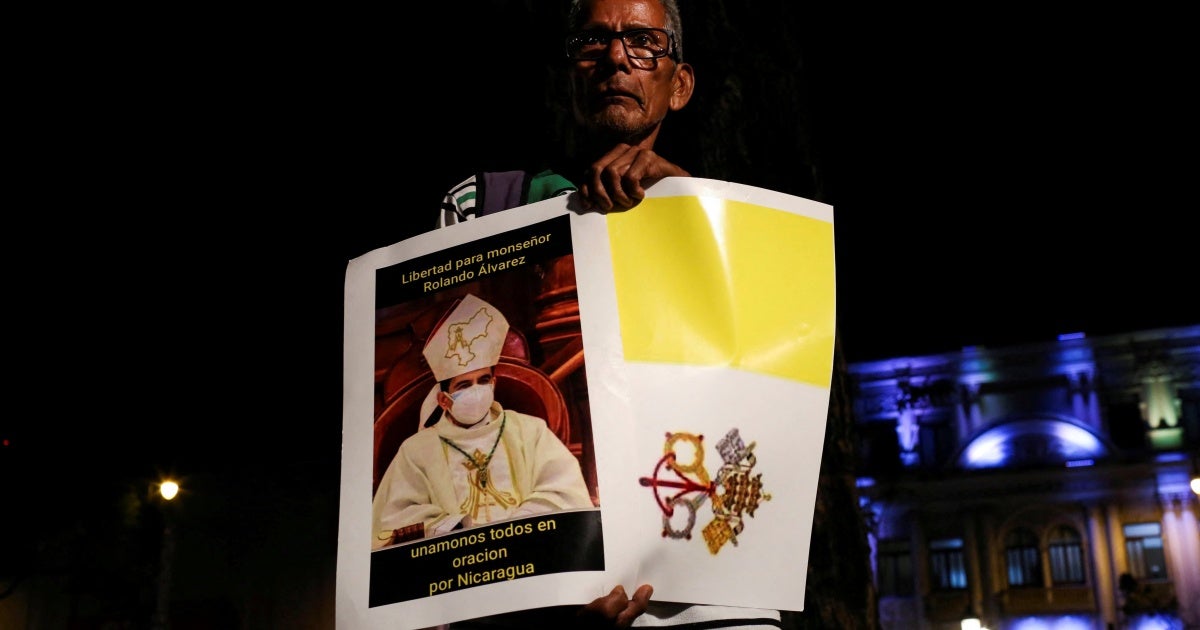

In August 2022, police detained Bishop Rolando Alvarez, an outspoken critic of the government, accusing him of “undermining national unity” and “spreading fake news.” In February, Bishop Alvarez refused to be expelled, and a judge sentenced him to 26 years in prison. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) reported in June that Bishop Alvarez was being held incommunicado.

Police said in May that authorities were investigating the Catholic Church for suspected money laundering and had frozen the bank accounts of several dioceses.

In August, authorities revoked the legal registration of the Jesuit-run University of Centroamerica (UCA), seizing its assets and leaving thousands of students in limbo. The closures bring to 28 the number of universities that have closed since December 2021.

In October, the government released 12 Catholic priests and repatriated them to Rome in accordance with an “agreement with the Vatican.”

Authorities have also banned Easter processions in 2023, closed a Jesuit religious order in August and confiscated its property, and continue to expel foreign priests and nuns.

Freedom of Expression and Association

Human rights defenders, journalists and critics have been targeted with death threats, assaults, intimidation, harassment, surveillance, online defamation campaigns and, as mentioned above, arbitrary detention, prosecution and deprivation of citizenship.

As of November 2023, authorities had closed more than 3,500 NGOs, including women’s, religious, international aid, and medical organizations, representing roughly 50 percent of the NGOs officially operating in Nicaragua before April 2018. The closures have disrupted vital services for many beneficiaries.

According to a report by the Nicaraguan NGO Network Platform, the government has shut down at least 57 media outlets between 2018 and 2022, with plans to close 30 in 2022 and two in 2023.

Many of the shutdowns were made possible by egregious legislation, such as the 2020 “foreign agents” law, which allows for the revocation of the legal status of organizations that receive foreign funding for activities that “interfere in Nicaragua’s internal affairs.”

Civil society groups reported that 23 journalists fled the country between April and June, bringing the total number of media workers who have fled Nicaragua since 2018 to 208.

Authorities have imposed restrictions that have hindered the operation of several newspapers, including censorship and blocking of access to printed material. Police have searched and seized assets of the newspapers Confidencial, 100% Noticias and La Prensa.

In August, a court sentenced journalist Victor Tikai to eight years in prison for undermining national unity and spreading false news.

Indigenous Peoples’ Rights

Indigenous peoples and people of Afro-descendant face discrimination, which is reflected in disproportionate rates of poverty, illegal encroachment on their traditional territories, and persistent violence.

In October, the Supreme Electoral Council stripped the indigenous party YATAMA of its legal status, accusing the party of “undermining Nicaragua’s national unity.” Police detained two of YATAMA’s key leaders, Brooklyn Rivera and Nancy Enriquez, in late September. Rivera’s whereabouts, who according to her family is YATAMA’s only representative in parliament, remained unknown at the time of writing.

Between August 2022 and June 2023, OHCHR documented eight violent attacks against indigenous peoples, particularly in the Mayangna-Sauni-As area of the Bosawas Biosphere Reserve.

In March, settlers attacked the Wiru community in Mayangna Sauni As territory, killing five people, displacing 28 families and setting all buildings on fire.

Settlers have taken about 21,000 hectares of land from the Miskito people and forcibly relocated about 1,000 people, likely to work in forestry and mining. Death threats have forced some indigenous people into exile, and the government has prevented some from returning to Nicaragua.

The Lama Creole Autonomous Region, which makes up two-thirds of the Indio Maiz Biological Reserve and is home to the indigenous Lama people and people of African Creole descent, is also under intense pressure from illegal cattle ranching.

Immunity from the 2018 crackdown

Police, working with pro-government armed groups, suppressed massive anti-government protests in 2018, killing at least 328 people, wounding about 2,000 and detaining hundreds more. Authorities reported that 21 police officers were killed during the demonstrations.

Many protesters were detained for months and subjected to torture and ill-treatment, including electric shocks, severe beatings, nail removal, choking, and rape. Prosecutions against protesters were marred by serious violations of due process and other rights.

No officers have been convicted of policing-related abuses.

Women and Girls’ Rights

Nicaragua has banned abortion under all circumstances since 2006. Anyone who performs an abortion faces up to two years in prison, and medical professionals who perform abortions face up to six years in prison. The ban forces women and girls to continue unwanted pregnancies, putting their health and lives at risk.

Restrictive abortion laws, combined with a lack of information and comprehensive sex education, are barriers to identifying sexual violence. In May 2019, an NGO presented to the UN Human Rights Commission the cases of two girls, “Susana” and “Lucia,” who had survived sexual violence and been forced to become mothers.

According to the OHCHR report, the incidence of domestic violence, violence against women and femicide (legally defined in Nicaragua as “the killing of a woman in the public or private sphere”) increased from August 2019 to December 2020.

The government did not release figures on femicide and other violence against women for 2022 and 2023. The OHCHR reported 36 femicide cases between January and June 2023, including four of girls under the age of 16.

Rights of people with disabilities

Discrimination against people with disabilities is widespread in Nicaragua. They face serious problems in accessing schools, public health facilities and other institutions. Nicaraguan law requires that 2% of civil servants must be disabled, but this percentage is not respected and employment opportunities for people with disabilities are few and far between.

Asylum seekers and migrants in Nicaragua

Between 2018 and June 2022, more than 260,000 Nicaraguans, more than 4% of the estimated population, fled, primarily to Costa Rica and the United States.

Many were forced to leave the country due to political persecution and lack of opportunities.

Key international actors

In April, the UN Human Rights Council renewed for two years the mandate of the Group of Human Rights Experts on Nicaragua and the reporting mandate of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, following the Group of Experts’ report in March which found sufficient grounds to believe that authorities had committed crimes against humanity, including murder, imprisonment, torture, sexual violence, forced deportations, and persecution for political reasons.

Pope Francis in March called Ortega’s government a “grotesque dictatorship.” The Vatican closed its embassy in Nicaragua in April after the country’s government proposed suspending diplomatic ties.

In September, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk reported that there had been a “continuous and widespread deterioration of human rights” and that the government continued to “punish and exclude those who express their views,” “deepening the country’s isolation.”

International monitors have not been allowed into Nicaragua since 2018 when authorities expelled the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights’ (IACHR) Special Monitoring Mechanism for Nicaragua, an interdisciplinary group of independent experts appointed by the IACHR, and the OHCHR.

Nicaragua participated in the European Union-Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (EU-CELAC) summit in July. It was the only country that did not support a clause in the summit’s final resolution expressing concern over the war in Ukraine. Russia has supplied Nicaragua with military equipment and security infrastructure over the past few years.

In September, the UN Green Climate Fund (GCF) board suspended funding for Bioclima, an environmental project that aims to reduce deforestation and increase resilience in the Bosawas and Rio San Juan Biospheres, after Nicaraguan NGO Fundación del Rio reported that free, prior and informed consent from indigenous and Afro-descendant communities had not been obtained. A final decision on the suspension of funding is expected in early 2024.

The US State Department’s July report on corrupt and undemocratic actors imposed sanctions on the Attorney General and congressional leaders. As of March 2023, the US Treasury Department has imposed asset freeze sanctions on 11 entities and 43 individuals, including government, congressional, and judicial officials. In April, the US State Department imposed sanctions on three judges who assisted in the revocation of citizenship for the aforementioned 317 Nicaraguans, and in August and September, it imposed sanctions on 200 city officials for alleged human rights violations in connection with the closure of the UCA and the Central American Institute of Business Administration (INCAE).

The EU renewed sanctions against 21 individuals and three state-related entities in October, and in June the European Parliament strongly condemned “the widespread, systematic and deliberate human rights violations perpetrated by the Nicaraguan regime against its own population for purely political reasons” and called for the release of all arbitrarily detained political prisoners.

The UK and Canada imposed sanctions on 13 and 35 people, respectively, for allegedly being involved in human rights abuses.

In November 2021, Nicaragua announced its withdrawal from the Organization of American States (OAS). Nicaragua withdrew from the OAS in 2021. The decision took effect in November 2023. In a resolution adopted in November, the OAS Permanent Council said it would continue to “pay special attention to the situation in Nicaragua.”