Located on Lemon Grove Avenue, a few blocks from the corner of Western and Melrose, this 1920s bungalow has a unique charm: The original hardwood floors are well-maintained, and the kitchen and bathrooms have been modernized.

On the market for $875,000, this Hollywood property featured in the 1970s classic “Chinatown” boasts being just minutes from the studio, and the world’s most famous sign can be seen from the dining room.

But despite being a relatively inexpensive property for the area, there was no interest, and in May the seller reduced the asking price by $50,000.

“Some people felt the neighborhood was an issue,” explained real estate agent Bobby Duarte.

A bicyclist rides along the tree-lined street of North Serrano Avenue.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Home prices are on the rise across the city, county and state, but in some areas of Hollywood and central Los Angeles, the opposite is happening.

Hollywood home prices fell 3% year-over-year in May and have fallen year-over-year every month since December 2022, according to Zillow data.

The median home price in Hollywood is $994,522, 8% lower than the highest price in the surrounding area.

Citywide, prices are near a record, 6% higher than they will be in May 2023. Countywide, prices are at an all-time high.

Zillow’s definition of Hollywood doesn’t include the Hollywood Hills, but it stretches primarily from La Brea Avenue east to Hoover Street and includes the area known as East Hollywood.

In the decade before the pandemic, Hollywood underwent a wave of gentrification: New businesses and people moved in, investors built new homes and renovated older ones, and housing costs soared.

Since then, changes have occurred: businesses have closed and complaints about homeless encampments have increased.

The exact reasons for the drop in home prices are unclear, but some real estate agents and residents point to a rise in homeless encampments, a desire to escape crime and more space than tiny bungalows and apartments offer.

Other areas seeing price declines include Arlington Heights, Downtown Los Angeles and the MacArthur Park neighborhood, which has densely packed apartment buildings and high crime rates. Firefighters found a man dead face-down in a park lake this month.

A graffiti-covered fence on Hobart Boulevard: Hollywood was undergoing a wave of gentrification in the decade before the pandemic, but that’s been changing lately.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

The San Fernando Valley has seen the greatest increases in home prices.

“The urban environment is wearing people down,” said local real estate agent Tracey Dorr. “People are looking for shelter.”

Duarte, the Hilton & Hyland agent representing the Lemon Grove Avenue property, said some people feel the neighborhood is less safe, but he doesn’t know why.

On a recent afternoon, the neighborhood’s streets were quiet and largely clean, except for one encampment about a quarter mile away.

Across the street from the house, at the Lemon Grove Recreation Center, kids were playing soccer and basketball in the park, and people were walking their dogs or lazing around in the sun.

Alex Weber, 39, who lives nearby, said he has never been a victim of crime but often sees prostitutes on Western Avenue at night and has seen the number of homeless encampments growing in the area in recent years.

Recently, the editor of a trade union publication told me that a couple had parked their old Hyundai Elantra on his street and left piles of trash on top of it.

“They were cool,” Weber said, “but if you go to look at a unit that’s just come on the market and all you see is a nasty scene of chaos and human desperation, I’m not sure it’s going to make a good impression.”

Studies have consistently found that high housing costs are a major cause of homelessness, and areas that are much poorer than Los Angeles but have cheaper housing costs have fewer homeless people, including areas like Jackson, Mississippi, and Huntington, West Virginia.

Even though rising homelessness has lowered the prices of homes for sale, it hasn’t made them affordable for most people: Fewer than 14% of households in the county can afford Hollywood’s median home price of nearly $1 million, and rents remain high.

Diana Huynak, 26, grew up across the street from Lemon Grove Recreation Center and still lives in the area.

“We’re barely getting by,” the psychology student says, “but it’s just getting gentrified.”

The Los Angeles Homeless Services Agency doesn’t currently break down the number of homeless people by neighborhood, citing concerns about accuracy, but it previously considered Hollywood’s homelessness problem to be so severe that it selected the city as one of three neighborhoods where it attempted to quantify the problem.

Brittney Weissman, executive director of the nonprofit Hollywood4WRD, said while it’s hard to track whether the overall number of people living on the streets in the neighborhood has increased since 2020, the organization has noticed an increase in homeless people suffering from mental health issues and drug-induced psychosis.

“It’s increased pretty dramatically,” Weissman said, citing methamphetamine’s easy availability as one of the reasons.

Stuart Gabriel, director of the UCLA Ziman Center for Real Estate, said the pandemic has increased demand for housing in areas with more space that are perceived as safer, and Zillow data shows that trend is continuing in Los Angeles.

The numbers also reflect Downtown’s shrinking role in the local economy, he said, as it still has a lot of vacant office space and fewer people need or want to live nearby.

Other economic factors may also be at play: The entertainment industry was hit hard during the pandemic and then again during the strikes and has yet to recover.

Vacancy rates in the Hollywood office market were 25.1% in the second quarter, up from 5.9% at the end of 2019, said Petra Durnin, head of market analysis at Ray’s Commercial Real Estate.

“It’s a painful adjustment period,” Durnin said.

A short walk from the Lemon Grove property, across from other homes and apartments, a row of tarps and tents line the sidewalk along a wall next to the 101 Freeway.

Tonia Gibson recently visited a friend who lives in one of the shelters, and said she also used to live in a camp but now lives in subsidized housing.

Although she felt safe when she lived there, she said, “I don’t want to buy an apartment so close to a camp.”

“When you don’t know who’s out there, you sometimes feel a bit unsure of your safety,” Gibson said, “especially when it’s dark.”

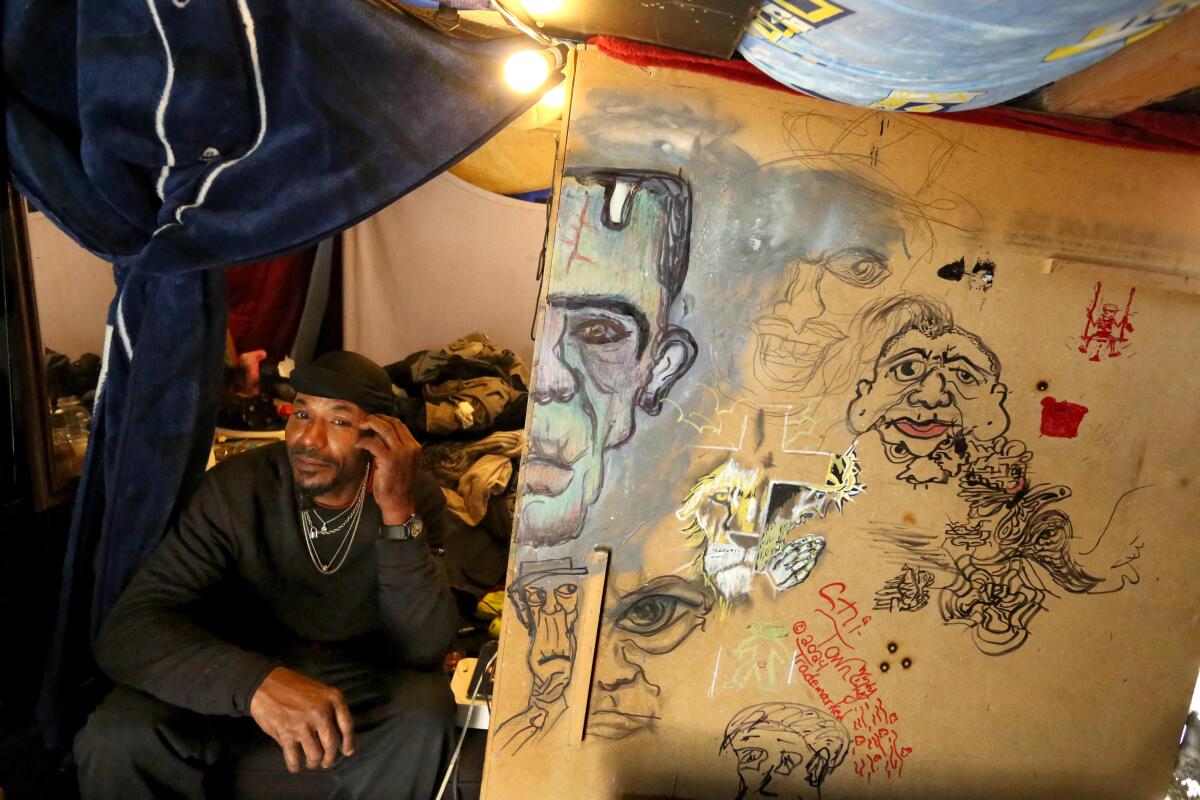

Alvin Young, 49, sits in a structure made of wood and blue tarps at an encampment next to the 101 Freeway.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Jason Gamble spent his days in front of tents and tarps, quietly searching for lamps and other items he’d found on the streets. He lives in a nearby plywood shelter and says heroin addiction led him to live on the streets seven years ago. Now 45, he’s beaten heroin but now uses crystal methamphetamine.

Elsewhere in Hollywood, homeowners have complained about encampment fires and said they feel unsafe walking through parts of their neighborhoods.

Kathleen Lawson, president of the Hollywood Partnership, a nonprofit that manages the business improvement district in Hollywood’s downtown area, said the area is turning around. She said Mayor Karen Bass’ Inside Safe program has made progress in keeping people off the streets, and the partnership is working on plans to increase street sweeping and hire more safety ambassadors.

“I’m very optimistic that Hollywood will be a lot cleaner and a lot brighter over the next year or so,” Lawson said.

Durnin said entertainment companies are also seeking office space in the neighborhood as production slowly ramps up, and technology companies are also moving into the market.

“Even if half of the companies that are considering it actually signed on, we’d be in a much better place,” Durnin said.

Some real estate agents believe the drop in prices is down to simple math, not tents.

Over the past decade, many developers have bought single-family homes in Hollywood, demolished them and built small subdivisions and apartment buildings.

Interest rates spiked and remained high in the second half of 2022, which increased development costs and reduced the amount homebuilders were able to pay for homes.

“There’s been a lot less investment capital put into the market,” said Dan Sanchez, a real estate agent with Engel & Völkers. “We’re not seeing the impact of homelessness.”

On Lemon Grove Avenue, the seller of a 1920s-era remodeled home got lucky, dropping the asking price from $875,000 to $825,000. Mr. Duarte said the house is currently in escrow, but declined to disclose the amount.

Back at the campsite on Highway 101, Alvin Young sat in a structure made of wood and blue tarps, with a couch, television and bed crammed into a space too small to stand in.

Young said he became homeless after splitting with his wife and his previous home was burned down. He said he was making ends meet by recycling and doing odd construction jobs and wanted to get off the streets.

“I don’t want to be here,” said the 49-year-old. “I want my own place. I want to renovate my house.”

Times reporter Doug Smith contributed to this report.