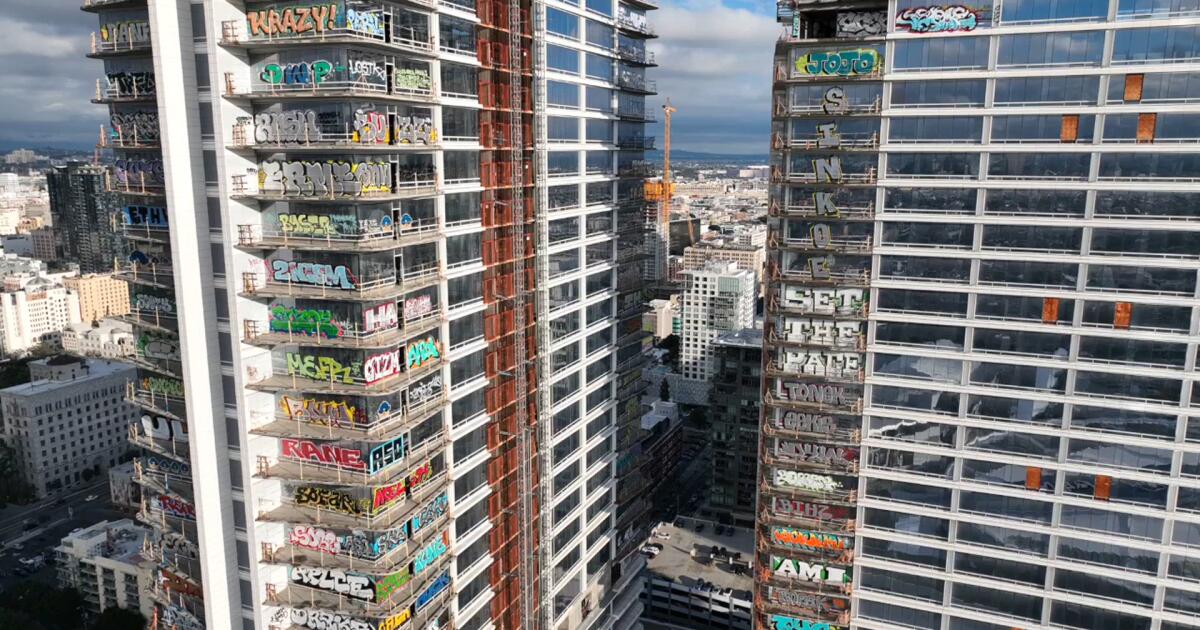

Graffiti is what made the abandoned high-rise buildings of Oceanwide Plaza in downtown Los Angeles notorious.

But illegal construction is the least of the problems facing the bankrupt, multi-billion-dollar development. As the possibility of a fire sale of the housing, hotel and retail project looms, a much more complicated and costly question looms over one of the region’s worst real estate disasters: Can the project be saved from demolition?

The quickest path forward for the new owners would be to complete the original plans for the three-building development, which was halted in 2019 and is now about 60% complete. But some potential buyers and construction experts say that plan would be financially unfeasible, mainly because the vast retail spaces on the project’s lower levels have few occupants and the oversized residential spaces on the upper levels would be extremely difficult to redesign.

An architect’s 2014 rendering of Chinese real estate developer Oceanwide Real Estate Group’s luxury project across from the Staples Center on Figueroa Street in downtown Los Angeles.

(RTKL Architects Inc.)

Instead, they say, the structure should be demolished to make way for something new.

“If there was a truly viable plan, someone would have proposed it,” said Bill Witte, chief executive officer of Related California. Mr. Witte said he believes Oceanwide has “negative value because of its size and the uncertainty of how much work needs to be done to complete it.”

In other words, he doesn’t think trying to restore Oceanwide Plaza is worth the risk.

But unfinished complexes in prime locations remain attractive to a small number of deep-pocketed real estate investors.

Last week, a federal bankruptcy court judge set the property up for auction on Sept. 17, citing multiple potential bidders.

The project’s market value is estimated at about $434 million, according to an appraisal filed by real estate brokerage Colliers in April during the bankruptcy proceedings. Colliers also estimated the cost of completing the building at $865 million.

Mark Turszynski, the Colliers broker overseeing Oceanwide’s sales effort, dismisses the notion that demolition is the only option. He predicted last month that whoever buys Oceanwide Plaza will complete it.

“About $1.2 billion has been spent on it and it’s about two-thirds complete,” he said, adding that engineers say it’s structurally sound. “Why demolish a project that’s perfect? It’s inconceivable.”

A photo taken on February 1, 2024 shows people applying graffiti to a skyscraper in downtown Los Angeles.

(Robert Gautier/Los Angeles Times)

For now, Oceanwide Plaza is a striking feature on the Los Angeles skyline, a graffiti-covered oddity on Figueroa Street, a wide boulevard that connects the downtown financial district with LA Live, Crypto.com Arena, and the Los Angeles Convention Center. It occupies a large city block across from the arena, making it an A+ location from a real estate perspective, right in the heart of year-round activity.

The site was once a vast asphalt parking lot used for events, but Beijing-based Oceanwide Holdings purchased it in 2014 with plans to build a luxury mixed-use development on a much larger scale than would typically be built in the United States.

Oceanwide broke ground on a complex that would house luxury condominiums, a five-star hotel, and an indoor mall with upscale shops and restaurants. The façade’s giant electronic billboard was supposed to bring a Times Square feel to Figueroa Street.

Javier Cano, area manager for Los Angeles Marriott Hotels, who oversees the JW Marriott and Ritz-Carlton hotels at L.A. Live, said the construction site wasn’t much of an eyesore when Oceanwide stopped paying contractors in 2019 and work halted.

That all changed earlier this year when graffiti artists invaded the building and turned the tower into a canvas for street art that made headlines around the world: colorful spray-painted murals on the floor-to-ceiling windows reach all the way up the tower, making it a sight to behold from miles away.

“There’s a wide range of reactions,” Cano said. “Some people believe it’s art, others think the exact opposite.”

He said the area continues to be bustling with concerts and games, but “we’re hopeful that something can be done in some way to bring life back to the Oceanwide Plaza area.”

Stuart Morkun, vice president of development for Mitsui Fudosan Americas, was one of several developers who explored ways to profitably acquire and complete Oceanwide Plaza but concluded it wasn’t feasible. As the builder of such big projects as the recently completed Figueroa Eight luxury condominium skyscraper a few blocks away, he said he was fascinated by the project.

“It literally feels like you’ve stepped into ‘Blade Runner,'” he said, referring to the 1982 film set in a dystopian future Los Angeles. “This post-apocalyptic environment could be from now, could be from anytime soon. It’s both terrifying and thrilling to see.”

Because the project has been subject to severe storms and other elements over the years, Molkun said he was surprised by what he saw when he toured the property while considering whether to make an offer on it.

“The concrete structure is holding up pretty well,” he said, adding that he saw little water pooling or mold growth in the drywall and that the aluminum and glass exterior has held up well to the weather.

Still, he says, unfinished construction projects are full of unknowns that can cause problems. “It can be daunting, like deciding to pick up a deck of cards in a card game. You might think, ‘Oh my God, what have I gotten myself into?'”

The biggest hurdle the new owners face in making Oceanwide Plaza economically viable is the design of the residential portion, which would have housed large luxury apartments. Oceanwide had planned to market the apartments primarily to Chinese expats looking to invest abroad, but the buyer pool shrank in 2017 when the Chinese government restricted capital outflows while the project was under construction. Selling large apartments has proven difficult in Los Angeles, where wealthy buyers tend to favor single-family homes.

Scott Johnson, an architect who specializes in designing high-rise buildings such as the Figueroa Eight apartment tower downtown and the Century City office tower, said converting living space from larger units to smaller, more affordable units would be extremely difficult because of the way the floors are laid out.

Construction on Oceanwide Plaza, a $1 billion mixed-use retail and luxury apartment project that includes three unfinished high-rise buildings, has stalled.

(Robert Gautier/Los Angeles Times)

To install the floors, builders used a common technique called post-tensioning, which involves pouring cement around taut steel cables that must stay in place after the cement dries.

“You can’t put 12 small units on a floor that has six huge units, because you’d have to cut every new toilet, every sink, every drain, every vent into the slab that has all the steel cables that support it,” Johnson says. “You can’t add more units here.”

If the number of units could be doubled somehow, the new developer would also have to determine whether the building has enough elevators, parking spaces and other amenities to accommodate the additional occupants, he said.

Real estate experts say using the property as designed will pose challenges beyond construction issues, mainly because of the sheer volume of space that would need to be rented or sold. Oceanwide is bringing to Los Angeles a plan on a scale that is more commonly seen in China, where developments often dwarf Western projects.

“The scale of this project was unprecedented,” Related California’s Witte said.

He described Oceanwide’s current state as “a remnant of overdevelopment.”

Witte was behind the recent megadevelopment in downtown Los Angeles, the Frank Gehry-designed Grand LA, a 1.2 million-square-foot, $1 billion complex in Bunker Hill that includes high-rise apartments, a hotel tower, and 176,000 square feet of retail space, including a chef-run restaurant.

Finding tenants will also be a big challenge for Oceanwide Plaza, which has more than 160,000 square feet of retail space it needs to fill with stores, restaurants and other uses, though more tenants have agreed to open this year but there’s still plenty of vacant retail space.

With many shopping malls struggling at the moment, leasing such a large space is daunting, and potential buyers are reportedly considering various solutions for Oceanwide, including turning it into a cosmetic surgery center.

Witte said that before the pandemic, he had calculated that Oceanwide’s retail space could be converted into office space for lease, as other Los Angeles malls such as the Sherman Oaks Galleria and the Westside Pavilion have done, but with downtown office vacancy rates rising, that option no longer makes sense, he said.

Morkun sought a novel solution to Oceanwide’s retail quandary: a casino. He envisioned it as one of a handful of casinos in the neighborhood, creating a mini-gaming district that would also help build nearby real estate projects.

“I thought the Lakers could be part of the ownership group for a casino and brand it Showtime Casino,” he said. “It’s right across from the arena, so it would be a very natural fit. The question would be, how do we get a gambling license?”

Morkun studied how other cities, such as Detroit, had attracted casinos in recent decades, but they couldn’t get around California’s restrictions that limited gambling to the territories of federally recognized Native American tribes. Morkun learned that the Gabrielino Tongva Indian Tribe, whose ancestral lands include the Los Angeles Basin, is not federally recognized.

Developer and landlord Scott Dobbins, who oversaw construction of the $500 million Circa high-rise residential building next to Oceanwide Plaza, said the residential properties should be rented as apartments, not sold as condominiums.

Apartment owners often sue developers alleging construction defects in their units or buildings, and the extended pause on construction on Oceanwide Plaza has multiplied those claims and concerns about liability, Dobbins said.

“I worry that with a project that’s been sitting around for five years, you’re going to get sued by a lot of owners,” he said. “Nobody’s going to insure you against liability lawsuits.”

Dobbins’ company, Hankey Investments, had been interested in buying the stalled development for years for what it considered a fair price, but “the price was basically zero,” he said.

Industry observers estimate that demolishing Oceanwide Plaza could cost as much as $100 million, a massive undertaking. If it goes ahead, it would be historic for the city of Los Angeles. Real estate data provider CoStar reports that the city’s Department of Buildings and Safety has no record of a building larger than Oceanwide Plaza’s height and size having been demolished.

Demolition expert Ken Terbolch said a dramatic explosive demolition like the one used to tear down the old casinos in Las Vegas would be impossible because the building is too close to other buildings.

It has to be done in phases, from the top down, said Taborch, project director for Penhall Corp., the contractor handling the demolition in Burbank.

“We used a small excavator and a small bobcat to remove it one floor at a time,” he said, breaking the building down to a size that would allow a chute to be dropped through openings such as elevator shafts, and once the building was low enough, a larger excavator could be brought in to finish the job.

Newsletter

Subscriber-only alerts

If you’re an LA Times subscriber, you can sign up to receive alerts about early or exclusive content.

Please enter your e-mail address

sign up

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.