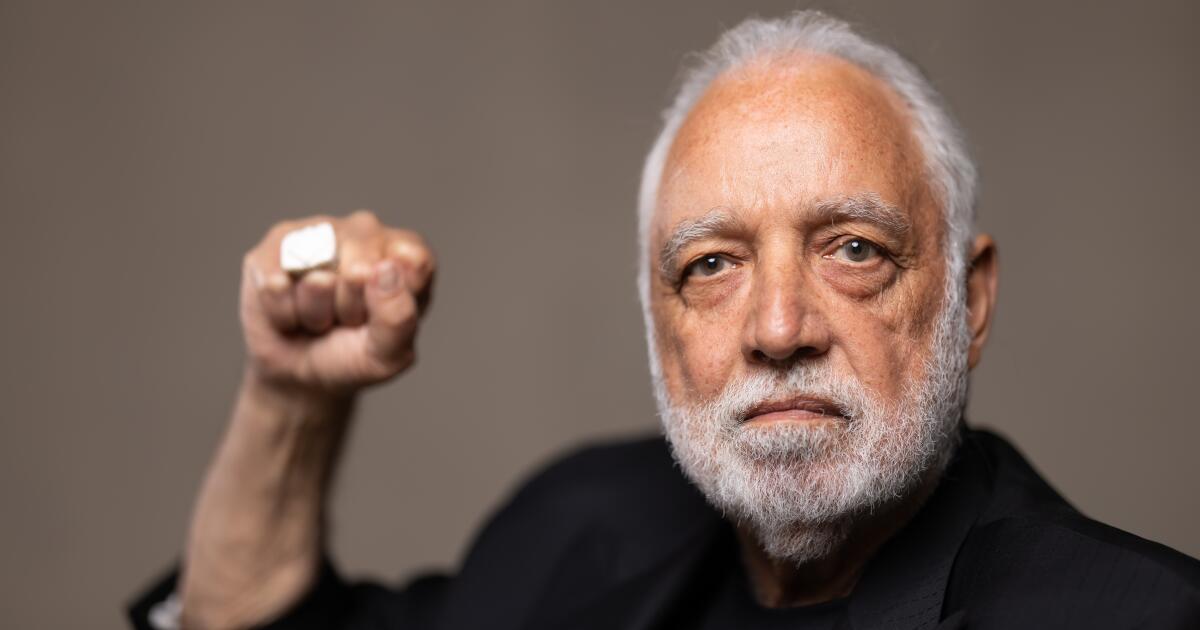

When Danny J. Bakewell Sr. left New Orleans for Los Angeles in 1967 at the end of the Great Migration, he was 21, a wife and baby, a college dropout and a time when the future for black people was bleak.

He would have taken any job here that would allow him to earn a living. What Bakewell didn’t imagine was that the job he got — a community organizer — would launch him onto a path to power as a civil rights leader, real estate developer, business mogul and publisher of the city’s legendary black newspaper, the Los Angeles Sentinel.

Discover the changemakers shaping all things culture in Los Angeles. This week, we bring you “Civic Center,” featuring innovative mayors, housing advocates, food providers and other pillars of Los Angeles. We’ll be bringing you the next episode every Sunday.

In the wake of segregation in the South, Bakewell quickly discovered that the City of Angels had its own racial hierarchy that left black people in rundown neighborhoods, under-resourced schools and brutal police.

Bakewell’s mantra was self-reliance, and he began rallying residents around that ideal in the late 1960s. “We didn’t want somebody to just hand us something,” he says. “We were prepared to work for it, and we were prepared to rely on each other for our future.”

A few years later, he was hired by the leader of the Brotherhood Crusade, a grassroots organization that refused government funding and funded self-help programs through voluntary deductions from black people’s paychecks.

“I am definitely an ally to Black people. I came to the table to serve them.”

— Danny J. Bakewell Sr.

The high-profile role raised Bakewell’s profile across the city and gave him the authority to operate from the halls of power to some of the city’s most troubled neighbourhoods.

He has the ear of politicians, including Mayor Karen Bass, and is respected in the community, and will never tolerate being ignored.

“Danny is always asking, ‘Brothers and sisters, what can we do?'” said Khalid Shah, executive director of the Stop Violence, Promote Peace foundation.

Mr. Bakewell, 77, helped legitimize the movement to turn gang members into peacekeepers, which helped curb violent crime. He brought commercial development to Compton’s rundown downtown and for 18 years organized Crenshaw’s Taste of Soul, the largest family-friendly food and music festival on the West Coast.

Still, Bakewell’s climb up the social ladder wasn’t easy: his single-minded focus on black issues and refusal to compromise unsettled some.

“I’m not against anybody,” Bakewell has always maintained, “but I am certainly for black people. I come to the table to serve black people, because I see us as always being left behind, always being left behind.”

“And if I take on a leadership role, I want to improve the lives of Black people.”