Introduction

By the end of 2015, an estimated 65.3 million people around the world were categorized as refugees, asylum seekers, or internally displaced persons (UNHCR [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees], 2016). In 2014, 28,064 people had applied for asylum in Austria. By 2015, this number had reached 88,340. Most of these people had fled wars in Syria or Afghanistan (BMI, 2017). Since then, the number of asylum applications has continually decreased and, in December 2019, reached 12,886 applications (BMI, 2019), while the number of forced migrants continued to increase globally (UNHCR [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees], 2019).

In this context, refugees, as Pisani and Grech (2015, p. 422) put it, are “often homogenized with little or no alertness to context, culture, religion, gender, but especially dis/ability.” Due to this, these intersecting attributes are seldom analyzed, specifically the aspect of disability. This is surprising, considering the WHO’s (World Health Organization, 2011) estimate that 15% of the world’s population is people with disabilities. Regarding refugees, (Help Age International Handicap International, 2014) reported almost twice the WHO global average in the number of persons with disabilities within the group of Syrian refugees residing in Lebanon and Jordan. The UNHCR also estimates that out of the estimated 70.8 million forcibly displaced persons in 2018, over 10 million have a disability (UNHCR [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees], 2019; Women’s Refugee Commission, 2019). Half of this displaced population is children (UNICEF [United Nations Children’s Fund], 2016). Based on these statistics, it is safe to say that refugee children with disabilities compose a sizeable group of individuals that belong to various disadvantaged groups simultaneously. Although no official statistics regarding the number of refugees with disabilities exist in Austria, the Monitoring Committee on the implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN CRPD) states that refugees with disabilities are a reality in the country (Monitoring Committee, 2016). Only a limited amount of research, though, has focused on the resettlement experiences and needs of refugees with disabilities in the respective host countries and the role of service providers (e.g., Roberts and Harris, 2002; Ward et al., 2008; Mirza, 2011; Flanagan, 2015; King et al., 2016). In the British context (Roberts and Harris, 2001, 2002; Ward et al., 2008), research has revealed the numerous barriers refugees with disabilities face when accessing help, particularly the inexperience of service providers. On the one hand, for example, few service providers for people with disabilities have experience working with refugees. On the other, service providers working with refugees have little experience working with people with disabilities. Other barriers include the inaccessibility of language courses, the absence of translation services, and a general lack of knowledge about rights and information about available services (from refugees themselves and the service providers). While this research has also revealed important support structures these refugees rely on—particularly immediate family members—it has tended to emphasize the experience of adults with disabilities and has thus overlooked the experience of refugee families with children with disabilities.

In the German-speaking context, in contrast, scholars have investigated the experience of immigrant families. While this research does not consider the specific situation of refugees, it is nonetheless valuable in providing a framework for future studies. Hedderich and Lescow (2015), for example, have examined the situation of immigrant families with children with disabilities in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, giving insights into the families’ experience with support services. Similarly, to the British context, one of the main issues obstructing these families’ access to support services was the language barrier. According to the authors, one of the best ways to counter this problem is to provide translators to the families, best done by what they call “cultural interpreters.” Khanlou et al. (2017, p. 1845) describes these individuals as “a person who works with the…[family] to help them understand the systems of service, complete paperwork for them, and inform them about available resources.” This culturally sensitive partnership (i.e., professionals understanding and appreciating families’ values, beliefs, and goals) is, according to Lindsay et al. (2012), essential for planning and delivering effective support to immigrant families. In her study about four immigrant families with children with severe disabilities in Germany, Halfmann (2012, 2014) revealed that support measures that target the entire family, and not just the child, were an extremely valuable tool for families to overcome issues of daily life. She also demonstrated that the problem of an “information deficit” on the part of the families resulted mostly from a lack of cooperation between various service providers.

King et al. (2013) report similar results in their international literature review on immigrant and refugee families of children with disabilities. In their review, they discovered a handful of studies (written since 1990) that examine these populations and only five studies that investigated the refugee experience. From these five, however, only one focused on refugee families and children with disabilities, while the other four concentrated on the mental health needs of young refugees, with family being mentioned only marginally, if at all. For the authors, the “most noticeable gap in the literature is the absence of work on the service delivery experiences of refugee children with identified disabilities” (195).

Moreover, King et al. (2013) state that the absence of accessible government and service information and the lack of knowledge about available support and benefits are some of the biggest challenges for immigrant families, including refugees. The lack of culturally adaptive service is another challenge, not only stressed by King et al. (2013), but also by other authors who have explored service providers’ perspectives on barriers and facilitators to providing care for immigrant families with children with disabilities (Lindsay et al., 2012; Khanlou et al., 2015; Brassart et al., 2017). Broadly speaking, the challenges described by these authors stem primarily from: (1) language barriers; (2) discrepancies in conceptualizations of disability between service providers and immigrant caregivers, (3) lack in providing culturally sensitive support; and (4) absence of trusting relationships.

More recent literature reviews exploring the experience of health professionals caring for refugees and asylum seekers in high-income countries came to similar results, stressing that language and cultural barriers and a lack of proper support and training for staff are the biggest challenges to caring for refugees and asylum seekers (Suphanchaimat et al., 2015; Robertshaw et al., 2017; Kavukcu and Altintaş, 2019). These studies offer similar recommendations to improving service to better meet the needs of refugees, including offering education and training for staff in order to provide culturally sensitive care, overcoming the language barrier by using interpreters, providing more information about the system and improving the links between healthcare services and community services.

These studies shed new light on the barriers in working with immigrant families from the families’ and service providers’ perspective. The studies also highlighted some strategies in order to overcome these barriers, but do not provide a description of a best-practice example where these recommendations were implemented. Nevertheless, both nationally and internationally, the intersection of refugee status and disability has not been sufficiently investigated (Pisani and Grech, 2015), specifically in the case of refugee families with children with disabilities. Research examining the challenges refugee families with children with disabilities face when in the host country interacting with social service providers and the degree to which services meet their needs are, to our knowledge, missing.

Due to this lacuna, this article explores refugee families’ social networks, their support structures, and presents a good-practice example. A survey was used to conduct interviews with experts from the BEAM project—one of the few Austrian organizations working at the intersection of disability and migration—and with the caregivers in refugee families with children with disabilities. This article presents the findings of our study, and hence provides new insights into the challenges faced by refugee families.

The article proceeds as follows. To begin, we explain the context of the study (design, research questions, the survey, etc.) explaining how the project developed, who participated in it, and how data were collected. Then, we present the findings from the interviews that were conducted. In this section, we describe the social networks—illustrated with the help of a sociogram—of three refugee families with children with disabilities. Context is provided to each family (how they arrived in Austria, education background, and previous experience with social support services) in order to gain a better understanding of their situation in Austria. Once this has been shown, we highlight the major themes that were discovered during the content analysis stage of the interviews with BEAM and the caregivers.

Study Context

This article is part of a wider study aimed at understanding the social network and the social support experiences and service needs of refugee families with children with disabilities who receive support within the BEAM Project. By working at the intersection of migration and disability, the BEAM project supports immigrant families in accessing social support and services for their children with disabilities and helps them navigate the Austrian social support system. The BEAM project is operated by an Austrian service provider. Since 2008, this service provider has been working in child and youth service as well as in the area of assistance for people with disabilities. The BEAM project itself began in 2014. The acronym BEAM stands for “Beratung, Begleitung, Behinderung, Eltern, Alltagskompetenz and Migration” (Consultation, Support, Disability, Parents, Practice Knowledge, and Migration). The social service provider, an Austrian municipality, and the Federal Ministry of Europe, Integration, and Foreign Affairs fund the project. The size of the project (based on the number of employees) depends on funding levels.

At the time of this study, the project team consisted of two groups: the core project team (a manager and two employees) and seven parents’ guides (Elternlotsinnen). The project manager (who also created BEAM) is a full-time employee for the service provider and dedicates 5 h a week to the project. The other core project members are employed between 10 and 15 h within the project. The so-called “parents’ guides” are a specific addition to the project. Originally, the parents’ guides worked on a volunteer basis. Over the years, though, as the project became more successful and funding for it increased, six out of seven parents’ guides were employed on a permanent basis (4 h per week). These parents’ guides are women who have migrant backgrounds and speak, as their native language, a language other than German. These guides are not only familiar with the language, culture and country of origin of the families, but also with the Austrian social support system. Therefore, the guides act as a bridge between different systems and can provide targeted support for specific families.

The Study: Aims and Research Questions

In addition to better understand the social networks of refugee families with children with disabilities and their social support experiences, we wanted to gain a better insight into the BEAM project. To do so, we investigated the perspectives of the caregivers, the children themselves, and the project team on the challenges faced by refugee families with children with disabilities trying to access social support and services. This article presents our findings on the perspectives of the project team and the caregivers. By doing so, we also shed light on how the BEAM project, specifically, has helped these families.

The following research questions are explored:

1. What is the composition of the caregivers’ social network around the family members with disabilities?

2. What challenges emerge for caregivers in accessing and utilizing social support and how were these overcome through the BEAM project?

3. What are the goals of the BEAM project and how are these achieved through support measures?

In this article, we distinguish between the concepts of social network and social support because information about the social network only provided information about the existence of specific support without specifying the support type (i.e., structural, instrumental or emotional) or whether or not the provided support was sufficient or helpful.

Study Design

In the larger project, qualitative data were collected from (a) four caregivers responsible for children with disabilities; (b) three children with disabilities; and (c) five BEAM project team members. Part of the data—the interviews with three of the caregivers and five project members—were used for this article. Purposive sampling was used to select the caregivers and project team members. The inclusion criteria for the caregivers in this article were: (a) refugee families (only caregivers who identified themselves as refugees); (b) individuals with official refugee status in Austria (approved asylum); and (c) caregivers (parents, siblings) of children/siblings with disabilities. The project members had to be actively involved within the BEAM project either by being part of the core project team (leader and employee) or as parents’ guides.

Recruitment

The researchers contacted the BEAM project leader and an invitation to participate was sent to all project members and families currently supported by the project. Subsequently, researchers contacted the participants who responded and agreed to participate to not only further discuss the project, but to also have participants understand and sign a consent declaration. This consent declaration also states that extracts from the interviews can be used for publication. At the beginning of each interview, the interviewer clarified that the participants could withdraw from the study at any time without providing a reason. The interviews with the project team members were conducted in German. Interviews with two of the caregivers were conducted mainly in German, but one caregiver sometimes expressed herself in English (Nalani). One interview was conducted with the help of an interpreter partly in German and Arabic (the native language of the caregiver). Quotes appearing in this article were translated by the authors from German to English if not otherwise stated.

Participants

Caregivers

In total, three caregivers, Nalani, Rahel, and Yassin (the names have been changed for publication), volunteered to participate in this study. All three caregivers arrived in Austria in 2015 and were granted asylum, and thus have refugee status in Austria.

Originally from Iraq, Nalani is 32 years old and is the caregiver for her two siblings, both of whom have a disability. The siblings are young adults (26 and 29 years of age). Though Nalani completed a bachelor’s degree in economics, she was unemployed at the time of the interview, but had completed an internship. Rahel is 35 years old, also from Iraq and the mother of a 7 year-old girl. She identified the disability of her daughter as Rett-syndrome. In Iraq, Rahel was a physics teacher in secondary education. In Austria, at the time of the interview, Rahel was unemployed, yet she was shadowing teachers in a secondary school while her qualifications obtained in Iraq were in the process of gaining formal recognition in Austria. Yassin is 42 years old and originally from Syria. He is the father of a 16 year-old boy, identified as having autism-spectrum-disorder (ASD). Yassin is an electrician but, due to qualification reasons, has not been able to pursue this in Austria and is currently working in the gastronomy sector.

Project Team Members

The team consists of five female participants, between the ages of 34 and 45. One of the participants is the project leader and mainly responsible for the management of the project and family counseling. Another participant is part of the management staff and responsible for family counseling. These team members are both Austrian and have degrees in education (specifically, special education and early childhood education). Both have worked as teachers in the respective area and as service providers for people with disabilities.

In addition to these project members, three parents’ guides were interviewed. The women are originally from Turkey, Afghanistan, and Egypt. They are employed 4 h per week in the project and are mainly responsible for supporting the families. Their educational background ranges from accounting to translation and working in social services. All participants volunteered for the interviews and did not receive compensation.

The Researchers

The researchers have worked or are currently working as service providers for people with disabilities. The first author has a migrant background and is a (former) refugee. This background helped in the construction of the interview guide and in the interpretation of the data.

Data Collection

All interviews were conducted in person in the BEAM project’s offices between March and April 2019. The same interviewer (the second author), in order to remain consistent, conducted all interviews. For each interview, open-ended questions were used. These asked for details of services provided within the BEAM project, and caregivers’ and providers’ perceptions on the challenges caregivers encountered in accessing social support for their family members with disabilities. The interviews lasted between 40 and 91 min, were audio-recorded, transcribed, coded and analyzed through qualitative content analysis (Flick, 2014) using MaxQDA. The interviews with the caregivers started with a sociogram and, for all interviews, an open-ended interview guide was used.

Using a sociogram in this study was beneficial, as it allowed the interview to get off on a good starting point. It was used to illustrate the social network of the families. The sociogram was adopted from Hedderich and Lescow (2014). It was introduced in the following manner:

I will now ask you some questions about yourself and your family. For this, I will use this diagram to illustrate your social network. Please tell me: What is your name, age, education and job situation? What is the name of your child/sibling with disabilities and the kind of support they need? Which people are important in order to provide support for your child/sibling and yourself?

Interview Guide

Two semi-structured interview guides were designed to explore the interviewees’ perspectives on the living and support situation of immigrant families with children with disabilities. Open-ended questions inquired about immigrant families’ experiences navigating everyday life in Austria, challenges encountered in accessing (social) support/services for the child/sibling with disabilities and the experiences with the BEAM project. The project team members were specifically asked about the goals and support provided within the BEAM project. Examples of questions include: “What does a typical day look like in your home?”, “What type of support is your child/sibling receiving?”, “What is the main goal of the BEAM project?”

The interview guide was influenced by research about immigrant families of children with disabilities in Switzerland (Hedderich and Lescow, 2014) and by the research team’s own experience working with refugee populations and children with disabilities.

Data Analysis

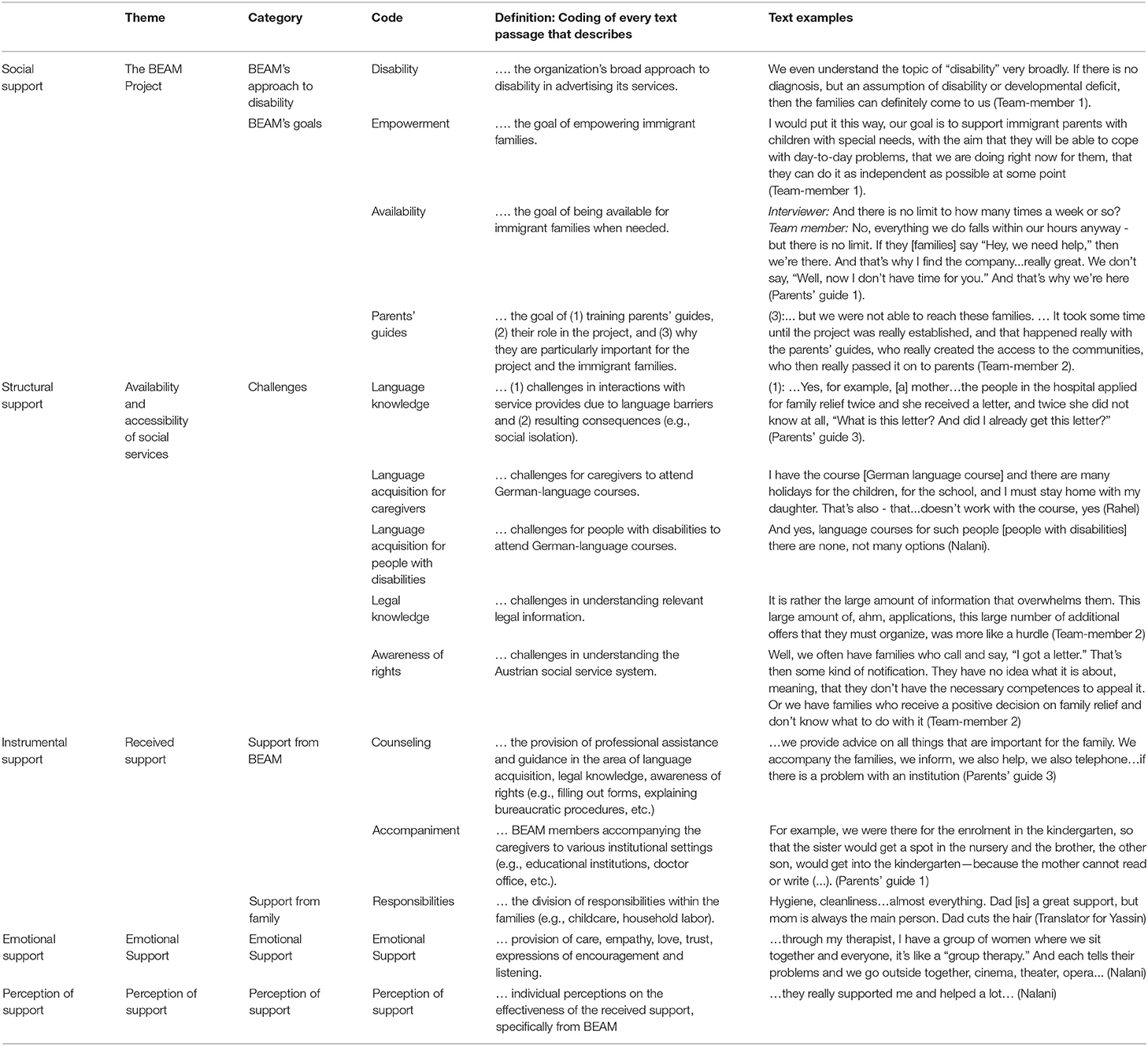

The analysis occurred in two steps. First, the sociograms of the three caregivers were analyzed in order to display the main network components for the caregivers of the person with disabilities. For this analysis, we used deductive coding and created a coding list with explanations of the codes before the analysis began. For this analysis we used Khanlou et al.’s (2015) framework of social support, which they adopted from House (1983). Social support is defined as: (1) “structural support” (knowledge of the availability of services for people with disabilities and how these are accessed); (2) “instrumental support” (services actually received); (3) “emotional support” (warmth and attention provided by people close to the family); and (4) “perceptive support” (individual perceptions on the effectiveness of the support).

Then, after all interviews were conducted, the two authors coded the transcript separately. The transcripts were analyzed using inductive content analysis (Mayring, 2000), enabling codes to emerge from the data itself. These codes were identified based on the frequency with which they were raised by both the caregivers and service providers. The following steps were followed: (a) the two authors coded the interviews separately; (b) they met then face-to-face, along with other colleagues, to discuss and define the codes; (c) during this meeting, a codebook was created, which guided further analyses; (d) after all interviews were coded, the authors discussed the analysis and sorted the codes into categories and themes. In this phase, the final version of the codebook was developed and enriched with two deductive codes (emotional and instrumental support) (see Table 1). After this meeting, a final analysis of the text occurred. The list of the emerged themes, categories, and codes together with definitions and text examples can be seen in Table 1. After all codes had been determined, we used Khanlou et al.’s (2015) framework of “social support” to help organize the codes for the article and link the results to the sociograms. For example, the theme “Availability and accessibility of social services” was placed under the header “Structural support” and the theme “Received support” under the header “Instrumental support.”

Table 1. The codebook.

Results

In this section, we first provide a description of the caregivers, followed by a description of their social network. Then, we give an overview of the challenges and how these were confronted. Finally, the BEAM project is described in more detail.

The Social Network

In this section, we first tell each caregiver’s story of why they came to Austria and their previous experiences receiving support for their children with disabilities in their home countries. Next, we show the social network of the three caregivers with a sociogram, which helps us illustrate the types of support the network provides them. This illustration is then shortly explained with Khanlou et al.’s (2015) framework of social support. Before describing the individual situations of the caregivers, however, it is important to note that two of the caregivers receive support from Austria’s Familienentlastungsdienst (Family Relief Services; FED). The FED, a mobile service that offers a range of support measures for families with children with disabilities (from domestic care to organizing leisure time activities), is funded by the individual state (90%) and the families themselves (10%) (Steiermärkisches Behindertengesetz, 2004).

Nalani’s Story

Nalani and her family came to Austria from Iraq. Nalani is 32 years old and the caregiver and older sister to her two siblings, a brother who is 26 years old and diagnosed with ASD, and sister who is 29 years old and diagnosed with an intellectual disability. Nalani studied economics in Oman and, for 4 years, had worked as an office manager. According to Nalani, she had a good life in Iraq before being forced to leave the country after her father died.

I had a beautiful life in Iraq…I used to earn…like…3 000 Dollar in a month, like more than my father. It is like – I had everything…but because my father died, we could not stand living there…and we felt insecure, we felt hunted, we felt like anyone would come and kill us. So, we had to come here and I – I gave it – I gave everything for them [the siblings]. (quote original English)

In 2015, Nalani came to Austria alone with her two siblings. After about 8 months, her mother joined them. The whole family now has refugee status in Austria, and Nalani has adult guardianship rights for her siblings. Her diploma has been recognized in Austria. During the interview, she stated that she was about to start a job in controlling and management. Moreover, she volunteers in two associations, where she teaches Arabic language and cooking courses.

Back in Iraq, Nalani described how her siblings had problems accessing education. Her brother could not attend school: “he was since birth like this…you see it immediately that he has problems.” Although her sister attended a regular school, teachers soon told Nalani that her sister was socially isolated from the class. The teachers complained that the sister “is very isolated, she cries a lot, she is not social, she is shy, she does not talk to anyone. She either cries all the time or smiles all the time.” After the teacher complaints, an IQ test was conducted on both siblings. The brother was subsequently diagnosed with ASD and the sister with an intellectual disability. According to Nalani, the teachers in Iraq were not familiar with how to teach students with disabilities nor did they possess the needed skills for it.

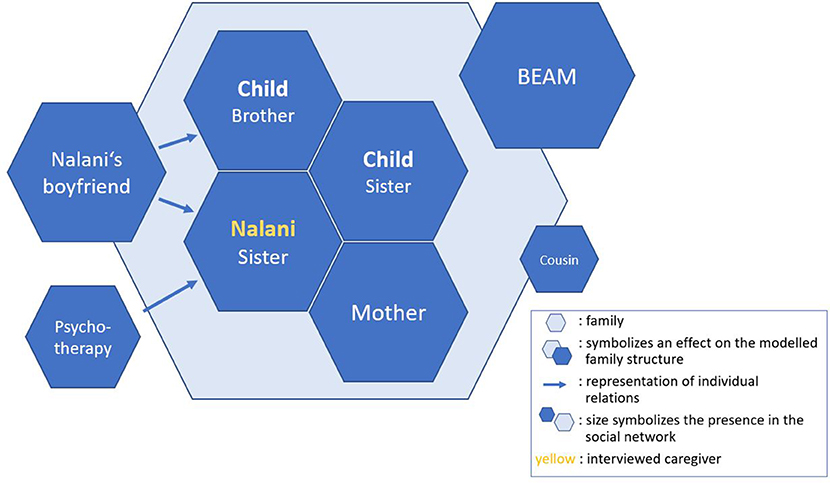

Nalani’s social network

Nalani’s social network in Austria is illustrated below (Figure 1). This social network was discussed with Nalani and jointly designed. It displays the people and institutions that provide Nalani social support for taking care of her siblings. The large, light blue hexagon represents the family structure. It includes Nalani, her siblings, and their mother. Arranged around it are the people who provide them support. The overlapping hexagons and arrows represent the impact support providers have. The size of each hexagon symbolizes the perceived impact of the support.

Figure 1. Nalani’s social network.

Structural support: Nalani describes BEAM as the most important source of structural support. Within the project, she received important information about different service options for her siblings, and the project team helped her find German language-learning courses for people with disabilities.

Instrumental support: Nalani mentioned multiple organizations and individuals as sources of instrumental support, including BEAM and, most importantly, her mother and her boyfriend. She also stated that her cousin, who lives in a different Austrian city, plays an important role, but only as an emergency contact. The psychotherapy she receives, moreover, is also included here.

Emotional support: Nalani receives emotional support mostly from her mother—who arrived in Austria 8 months after her and her siblings—and her boyfriend. Through the psychotherapy, she also met a group of women she spends her free time with.

Perception of support: In taking care of her siblings, Nalani perceives her mother and boyfriend as a great source of support. She also states that BEAM as an important source of information and support to help her access social support.

Rahel’s Story

Rahel is 35 years old and the mother of a 7 year-old girl diagnosed with Rett-syndrome. The family is from Iraq. In 2015 Rahel, her husband—who studied hydrochemistry in Iraq, worked in telecommunications and is employed in Austria—and her daughter had to flee the country because of war and a lack of medical care for her daughter. They are also recognized refugees in Austria.

Rahel has a university degree in physics, and she was a physics teacher in Iraq. During the time of the interview, her diploma was in the process of being validated by the Austrian government, which would allow her to eventually pursue her work. To work in the Austrian school system, she also must possess C1 level German skills. For the last 2 years, she has been attending language courses. In addition to this, she shadows teachers in a school to become familiar with the Austrian school system.

In Iraq, the daughter attended a kindergarten. Rahel had a negative experience with the kindergarten. According to her, “they did not take good care of her, she came home wet, always…because she could not drink alone, and the kindergarten assistance did not help her.” After her daughter was diagnosed with Rett-syndrome, Rahel quit her job and stayed home with her because the kindergarten did not offer support for children with special needs. After arriving in Austria, her daughter had to wait a year in order to receive a spot in a kindergarten. During the time of the interview, the daughter was enrolled in the first grade in a special school.

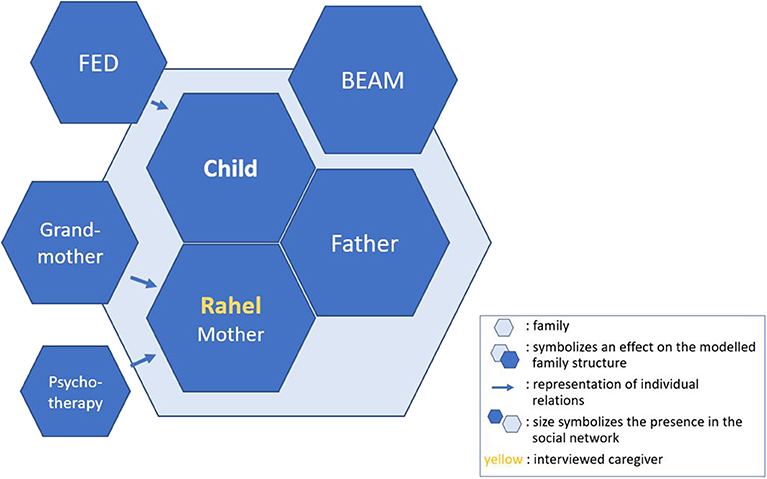

Rahel’s social network

Figure 2 represents Rahel’s social network, illustrating the individuals and organizations that provide her social support. The sociogram, designed from Rahel’s point of view, reveals which sources of support are important for her. Her daughter is in the center of the sociogram. Arranged around the daughter, are people who provide support in different ways to Rahel to take care of the daughter. The large, light blue hexagon represents Rahel’s family. The impact of support providers is illustrated by overlapping hexagons and arrows. The size symbolizes the perceived impact.

Figure 2. Rahel’s social network.

Structural support: For Rahel, BEAM is the most critical source of structural support.

Instrumental support: Rahel described her husband, who helps her with caregiving and providing for their family, as her main source of instrumental support. She also qualifies for welfare support from FED and BEAM. Although she did not mention any friends who provide instrumental support, her psychotherapy plays a minimal role here as well.

Emotional support: Her husband and Rahel’s mother, who lives in Iraq but with whom Rahel talks with over the phone daily, provide this type of support. The parent’s guides from BEAM also have an important role here.

Perception of support: Rahel feels that BEAM’s support has been extremely helpful in taking care of her child.

Yassin’s Story

Yassin is 42 years old and the father of two children, a son (16 years old) and a daughter (11 years old). His son has a disability, which Yassin identified as ASD. The family is from Syria, where Yassin worked as an electrician. In Syria, his wife stayed home and took care of the household and their children. Although his son attended school in Syria for the first and second grades (7 to 9 years of age), Yassin and his wife soon removed him. This was because, according to Yassin, “the teachers wanted more money to support him.” Yassin’s translator, who accompanied him during the interview, also stated that the family “couldn’t pay anymore for the school, his whole salary was going to that school, how could they live then?” Yassin explained that all of the support they received in Syria was private. They visited several doctors, and the son received numerous therapies, all of which were very expensive.

In 2015, the family fled Syria to Egypt. While the family remained in Egypt, Yassin went alone to Turkey, and then to Greece, onto Serbia, and finally to Austria. After 5 months in Austria, he managed to get his family (wife and children) to the country. He also mentioned that his in-laws also live in Austria. After arriving in Austria, the family first stayed in a refugee camp and the son was immediately enrolled in a school. After receiving their refugee status, the family moved to a city in Austria where they encountered BEAM within the first 10 days.

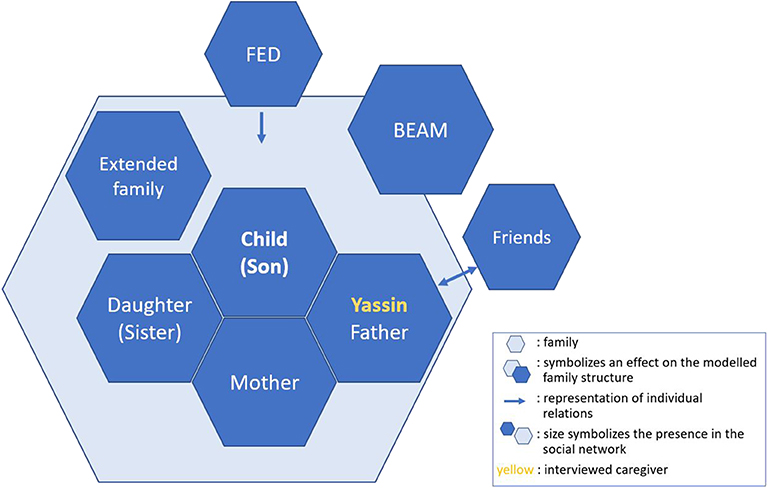

Yassin’s social network

Figure 3 represents Yassin’s social network. It displays the individuals and organizations that provide him social support. The sociogram, designed from his point of view, reveals which sources of support are important for him. The large, light blue hexagon represents his family. The impact of support providers is illustrated by overlapping hexagons and arrows. The size symbolizes the perceived impact.

Figure 3. Yassin’s social network.

Structural support: As with the other interview partners, BEAM played a critical role in offering structural support to Yassin.

Instrumental support: Yassin stated that BEAM helped not only his son with disabilities, but also with his daughter, specifically in finding a spot for her in a school. He also received support from the FED. His wife was described as the primary caregiver, and his daughter supports the parents in various activities.

Emotional support: This was provided by his immediate family, his extended relatives, and BEAM team members. Furthermore, he is the only caregiver who mentioned that friends also offer emotional support.

Perception of support: Yassin perceives support provided by BEAM to be incredibly helpful, and he is glad that he discovered BEAM soon after his arrival in Austria.

Now that each caregiver’s support structure has been briefly shown, the following section will provide more detail about each aspect of this support.

Structural Support

In this section, we describe the interviewee’s perception of the availability and accessibility of services. In the interviews, the participants mainly discussed the challenges in accessing structural support. This section highlights the reasons given by the participants.

Interaction With Service Providers: Language Barriers

Caregivers and team members both perceived a lack of German knowledge as a challenge for refugee families in accessing services. As one BEAM team member said:

So, families that really are not good at German, there are…many, many, huge challenges. So, I realize how hard it is during the consultation, we are always dependent on someone translating, either a interpreter, friend or a parents’ guide. And I can imagine that in everyday life, when they have other appointments and they really cannot make an appointment without a translator, whether they need to go to school or a routine exam… really nothing is understood there when nobody is with them. That’s actually the biggest challenge, I think… I just believe that if you can handle the language well, you automatically become more independent.

According to team members, not speaking German leads to caregivers being dependent on external help—an official translator, a friend or a parents’ guide—in order to attend important meetings and to understand what they are being told. Although learning German is perceived as the pathway to independence, if the language has not yet been acquired, it also leads to social isolation. Language barriers impede the participation in the wider community and in children’s school lives. According to one team member:

Yes…from our experience it is almost always the language that hinders true participation. Specifically, when it is about establishing contact with other parents…you could have a lot of social contact through kindergarten, school and… this is not happening…because they [caregivers] are not confident enough to go to a teacher-parent conference and talk to other parents.

The five team members also described this insecurity, and explained that caregivers, even after acquiring German language skills, are unsure if they understand everything correctly. The parents’ guides also describe the complexity of the issues refugee caregivers of children with disabilities are affected by, as seen by the quote below.

The families are extremely stressed due to the language “Have I understood everything? Have I understood right?”…Yes, it is stressful for the families, and then having a disabled child, it is a long list: appointments with doctors, therapy, speech therapist and other things and they don’t speak German…

This quote highlights a major consequence of not understanding German: it puts a large amount of stress on the individual caregivers. According to the team members, this stress becomes compounded for the caregivers, since they are raising a child/sibling with disabilities and, due to this, need to access particular social services more often and from various sectors (e.g., health care, school system, therapy, etc.)

Interestingly, the ability to communicate in English does not seem to help, either. As Nalani explained:

I would go to the authorities and ask “Do you speak English?” and when they would say “No, you are in Austria, you can only speak German,” and I would say: “Okay, ja, I know, but in the beginning I need to explain something.“[original English]

Worker: “No, I don’t speak English.”

Nalani: “Okay, but you understand the English, you understand me?” [original English]

Worker: “No, I don’t.”

So, it was very stressful for me, because they are not helpful, and they expect me to know everything from the beginning [since her arrival in Austria] and that is a challenge for me. I came to Austria by myself with the two [referring to siblings], without mama.

As Nalani’s comment brings to light, the service providers, in particular the government bureaucracy, do not seem to want to use English. As her description reveals, however, it does not seem to be a question of competence. The individual employees understood her questions posed in English. Nevertheless, this language barrier can be understood in multiple ways, either as an unwillingness to communicate in a language other than German in an official capacity or as an inability to do so. Whatever the case may be, this left Nalani with a negative view of Austria’s service providers. Furthermore, she highlights being stressed and left alone in caring for her siblings.

Learning the Language: Structural Problems

Even when caregivers want to learn German, the process of doing so remains difficult. Both Nalani and Rahel—and all team members—stressed that German language course providers do not take into consideration the challenges of refugee families’ daily lives. Specifically, refugee families—in our case, the three caregivers described here—often do not have a large social network that they can rely on for issue such as childcare when they have to attend a language course. Due to this, these courses remain inaccessible for most caregivers with children with disabilities. One parent guide explained the problem this way:

It would be a tremendous relief for the families if there would be more German language courses with childcare included. It would be much, much easier for families, because a lot of parents stay home because of their children. A lot of them want to learn German, but they can’t because there is no childcare. Most of the families do not have anybody here, no mother, sister, grandmother who could take care of the children…specifically families from Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan are burdened…

The caregivers echoed this problem, too. Nalani, for instance, said she could only start taking German courses once her mother came to Austria, that is, once she had someone who could take care of her siblings while she was in class. Likewise, Rahel stated that, early on, she had to stay home and take care of her daughter while her husband could attend German courses. In both cases, a decision needed to be made who would attend a German course first, or at all, and who would stay home and take care of the children. Though over the last 2 years, Rahel has managed to be able to attend a language course, she still finds it difficult to balance the language course and her caregiving of her daughter.

I have the course [German language course] and there are many holidays for the children, for the school, and I must stay home with my daughter.

Since she cannot rely on any other individuals—her husband is employed full time—when there is a conflict with her daughter’s school calendar, she must stay home with her and thus misses the opportunity to improve her language skills. Even though she has FED, this support is not enough, since the language course is four times a week and she states “I cannot leave my daughter with FED from 07:30 a.m. until 1.00 p.m. That’s too much.”

The school calendar also proved to be an issue for families, namely the afternoon school care for children in the case if a parent is unemployed. The following statement by a team member is describing a case of a mother and her struggle to participate in a German course:

She [the mother] wants afternoon care for the children in school. The reasoning [from the responsible authorities] then was “why should we pay afternoon care, when the mother is at home?” So, it is not easy, it won’t be paid for, when one parent is at home. And then…she has issues with the…[employment service in Austria], they told her, she will only get a job if she can prove that she has afternoon care for the children and on the other side she will get the afternoon care if she has a job…that is hard!

This statement is an example of the bureaucracy the parents have to deal with. On the one hand the immigrant families will not be able to get a job or a qualification without sufficient knowledge of the German language. On the other hand, they cannot participate in the courses due to their obligation with their children. The schools however could take care of the children in afternoon care. The parents cannot afford afternoon care without support from the government, which they will not get, since the mothers (usually the mothers) are unemployed and can stay with the children at home. The team members stated that this issue is mainly present with refugee families and immigrant families without a support network, since they do not have family or friends who could take care of the children for them.

Language Barriers: People With Disabilities

Language barriers are not only an issue for the caregivers, however, but also for the children with disabilities. As Nalani explained, language acquisition proved to be an issue for her siblings. Since Nalani’s siblings, who are 26 and 29 and no longer school aged, she tried to find them a sheltered workshop. Every well-known, large service provider in the city they lived in, however, refused them because of her siblings’ lack of German knowledge. As she explained:

In the beginning, I researched a lot and went to every organization responsible for people with disabilities [the names were anonymized by the authors]. They all told me: “They [referring to the siblings] cannot [be here], they need to have knowledge of the German language. They can’t interact with others, or in the sheltered workshop” …I was then searching for a German language course for people with migrant background and a disability.

It is also important to note that not only did these organizations reject Nalani’s siblings, but they also did not provide her any information regarding other possible opportunities, where and if language courses for people with disabilities were offered. This brings to light another recurring issue. On the one hand, language skills are required to participate in daily activities. Yet, on the other, little opportunity exists to improve these language skills. That these organizations did not provide Nalani with any information regarding language courses for people with disabilities, moreover, highlights the fact that migration issues and disability issues are treated as separate areas with their own special services, leaving those who need help in both in a conundrum. Nalani first found out about the needed language courses through BEAM, who not only told her where she could find them, but also offered them themselves.

Barriers to Legal Knowledge

In addition to German language acquisition, another large hurdle for caregivers was a general lack of knowledge about what their status as caregivers of children with disabilities provided them. The team members stressed that the caregivers were unaware of what to expect from the Austrian social system and what the system expects of them in return. Awareness of their rights was almost completely absent, which is understandable considering these families recently arrived in the country. One parents’ guide explains this issue as follows:

The families in the BEAM project now have information they never had before. Many families [say]: “Really, my child has rights? … that is great.” Yes, that is new information that was never there before.

According to the BEAM team members, the families want services that can help their children, including a spot in school, general support, and specialized therapy. But the team members also tried to broaden the caregivers’ scope of what is possible in Austria. One team member said:

An important goal, what most parents can’t even imagine, is to see perspectives for their children. We try to raise that awareness because a lot of cultures don’t…have inclusive schooling…there are no workplaces for people with disabilities, independent living…and so we say: “Okay, the goal is that your child will live independently”…these goals, are often goals that need to be awoken in the parents, because they don’t know what that means. It doesn’t mean that the kid goes to school now and after the school is done, the kid is home and the mother takes care of him or her…the goal is then, “I am supporting my child, to do a lot on their own, that he or she is independent of my help once I am done”…these are topics that are not available and we need to say: “In Austria you have these possibilities and there are possibilities for the child.”

As this quote demonstrates, BEAM is not only providing information about possibilities within the Austrian social system, but it is also helping caregivers to understand concepts such as independent living or empowerment of their children. According to the team members, this is necessary because the caregivers have never resided in a place where these types of support structures exist, which has usually resulted in children being solely dependent on the caregivers. It is not just information that is provided, then, but also awareness about what is possible for children with disabilities living in Austria.

Awareness of rights is also important, as is an understanding of the range of the various support systems. The following example from Rahel illustrates the lack of knowledge many families have when it comes to understanding the roles and responsibilities of the various actors within the social system.

She [the daughter] had early intervention once a week… it was one woman; she came to us and played a bit with my daughter for an hour. But she did not really do that with daughter, she talked more to me…drank coffee…I did not know, “What is the law here and what is she supposed to do?”

Rahel’s quote illustrates the necessity to help caregivers understand the different roles of the service providers and what type of support is being provided at what point.

For Rahel, though, this issue continued once her daughter was enrolled in school. Although her daughter is legally entitled to one in Austria, she does not have a teaching assistant, which, for Rahel, is not perceived as an issue. “Teaching assistance, just for her?” Rahel said, “no, no, although she would need it, I think, but that is expensive, I mean for the municipal authorities.” Once again, Rahel, as the caregiver, lacks critical knowledge of the Austrian system, which, unfortunately, none of the service providers provided to her.

All of the issues described above—German language opportunities for caregivers and their children, knowledge of the rights afforded to children with disabilities—are tied to the problem of receiving helpful information and guidance. As Yassin said:

Because I do not understand what is happening, for these medical reports or the mail [the letters the family received for the son], I always ask: “What is this, what do I need to do?”

In one way or another, all caregivers would, on the one hand, be told to do something, but, on the other, would never be instructed how this could be accomplished. Moreover, when information was provided to them, it was often of little consequence. According to Rahel:

When I had issues, they [a service provider] didn’t do anything for my daughter…they just checked what possibilities I have and read it for me. I do that myself. I can read at home what there is and what isn’t…they just search what is available, and I can do that, I can do research… BEAM actually helped.

Rahels’ quote illustrates that besides providing the information, the caregivers need instruction on what to actually do with the provided information (i.e., what steps can be taken to access specific support structures).

When it came to instrumental support, however, all three caregivers identified BEAM as their main source of this type of support, which had been missing in their interactions with other service providers.

Instrumental Support

The Role of BEAM

BEAM not only provided information about what the Austrian system offers refugees with children with disabilities, but it also helped them fill out forms and applications for services they qualified for. This was important, because, as stated earlier, all three caregivers needed help with German (particularly, legal documents) and BEAM helped to bridge the language barriers using the parents’ guides. Nalani describes her experience with BEAM in the following statement:

And then I found BEAM… They told me, “We offer this and that, but first we need the assessment,” and she [a team member] showed me where I can make the application, what the government offers. I was thrilled, because I had no experience and as a person without friends, without people, I couldn’t have known that.

In this statement, Nalani describes that in order to access the available services for her siblings, she needed a formal assessment of the specific degree of disability. She stated that every service provider told her this, but that nobody explained to her what that meant or how to get that assessment. BEAM provided the help she needed. The team members did not only explain what the assessment was, but (they) also described the process of getting it, what forms are required, to whom these must be submitted, and even accompanied her to the various appointments. In addition, Nalani touches on a major challenge facing refugees in a host country: the lack of a social network. Nalani describes herself as a “person without friends…”, highlighting the isolation that refugee caregivers experience when caring for their children/siblings with disabilities. This again underlines the need of providing adequate support for refugee caregivers who are in these situations, not only coping with resettlement but also with the specific demands of caring for a child/sibling with disabilities.

Even in specific situations in school environments, BEAM played an important role in providing instrumental support for Rahel. In one incident that Rahel described, her daughter swallowed a balloon when she was in kindergarten, which she and her husband discovered when changing her diaper later in the day. In order to address this issue with the employees of the kindergarten, a BEAM project team member accompanied her.

Yes, that was in the kindergarten…with a BEAM team member we went there and had talk with the head and a pedagogue…they were afraid, I don’t know why. We did not complain…we just wanted to say, that they need to take better care of our daughter, more attention…

Rahel noted that the care of her child improved after that visit. It is important to note that Rahel did not confront the kindergarten by herself but with a BEAM team member. This suggests that a large enough language barrier existed between her and the kindergarten so that she could not communicate her demands, or that perhaps she felt as if she would not be taken seriously on her own without the presence of a (professional) service provider. The sentence “they were afraid” could allude to the latter. She also noted that BEAM team members also accompany her when she tries to resolve problems with the school her daughter currently attends (her daughter is now in the first grade). BEAM has also been helpful in organizing transportation to this school for Rahel’s daughter.

The Role of Family

The team members stated that most refugee families do not have family members in Austria to provide instrumental support. This was also illustrated in the previous results when the caregivers themselves described the lack of a social network. The three caregivers, however, stressed that the family they did have with them was incredibly important. Nalani, for example, stressed that her mother offered this support, and she and her mother split the household and childcare responsibilities as the following quote shows:

Mom…she cooks, cleans, provides care, support and…I am doing, doctors, [going to the] authorities, teacher-parents day, events…

For Rahel and Yassin, spouses are important sources of support. Both speak about their division of household labor and their shared childcare responsibilities. Nalani, moreover, describes her boyfriend as someone who helps with her siblings (e.g., planning leisure time activities, specifically with the brother).

Emotional Support

For all three caregivers, family was the largest source of emotional support. In Nalani’s case, her mother played a critical role, enabling her to participate in German language courses, pursue employment, and have free time.

… and then when mom came to Austria, I could go outside, go to a German language course, meet new friends and so on, you say integrate…

For Rahel and Yassin, spouses are also important sources of emotional support. However, both also mentioned the family that they left behind, with whom they talk on the phone, also gives them strength. Yassin sees, moreover, his friends as important people in his life, while Nalani describes her boyfriend and therapist in similar terms. For Nalani and Rahel, psychotherapy was also described as important in order to cope with everyday stress of caring for a child/sibling with disabilities during resettlement. For Rahel, BEAM team members also provide emotional support, which is explained in the next section.

Perception of Support

All three caregivers perceive BEAM as their only sufficient source of support. Without BEAM’s help, they all explained that they could not have received further support for the child with disabilities and themselves. According to Nalani:

Yes…without the two [project head and team member], the support, I could not do or know “What is the next step?” They helped a lot.

Rahel, likewise, perceived BEAM as critical. Yet she took this a step further, and saw BEAM project members not only as supportive, but almost as belonging to her family:

I don’t see them as service providers, I see [them] as sister or family, relatives, that are not only supporting me with paper and so on, she supports me – I see that – with heart and yes, with much love.

BEAM team members also share these perceptions. All team members stressed that they often are engaged with the families beyond their required working hours. As one parent guide described it:

I am doing a lot on voluntary basis and I know that is not my working hours, but still…this compassion for people doesn’t let me stop. I assist…and when I receive a call and a woman has a lot of issues, I support, and don’t say “no.”

As this quote demonstrates, these parents’ guides clearly develop close relationships with the families.

The BEAM Project

In the previous section, we have shown challenges confronted by caregivers when interacting with service providers and how these were overcome through support from BEAM. In this section, we elaborate on these support measures from BEAM. First, however, the goals of the BEAM project and how these developed are explained.

In order to understand what type of support BEAM provides, it is important to show how BEAM changed its way of working with its clients through its interaction with immigrant families. It is particularly interesting that not only the way the team members approached immigrant families changed over the time, but due to this, the name of the project itself changed. According to one team member:

… the project BEAM was originally called “Behinderung, Eltern, Alltagskompetenz und Migration” [Disability, Parents, Practice Knowledge and Migration]. We have made that B for Behinderung [Disability] deliberately smaller on our info material and made Beratung and Begleitung [Consultation and Support] larger because we have seen that it [disability] is a big hurdle for parents. Although when they know that they have a child with disabilities, this disability needs to be very severe for them to use the word disability. The feedback we have received from different cultures and languages is that disability is mainly something visible. Meaning, a child sits in a wheelchair, a child has multiple severe disabilities; then it is a disability. Everything else (is) in the language is called something different. So, the word disability would not be used in everyday language and that is why we are trying to take the focus out of that word and…just support the child.

After working with individuals with a range of backgrounds, this quote demonstrates that the service provider is actively engaged with their clients. While the service provider initially had a particular view of what disability meant, after interacting with these individuals, they realized their conception of what it meant to have a disability did not connect to the daily experiences of their clients. Due to this, the service provider changed the name of the project in order to reflect this. This “name change” demonstrates that the project team is actively engaged in providing culturally sensitive support for their clients through dialogue with their clients and parents’ guides about what disability means. Through this process, the team members realized that gaining access to immigrant families with children with disabilities is not an easy task, and that they need individuals from these communities to establish contact and transmit the necessary information to the communities. As one team member explained:

And back then, when the project was submitted for funding it was only supposed to provide consultation. During our work we have seen the need to train women from communities [with different languages] that will provide us access to the families and get the information to the communities.

This development of the project resulted in training women from different language backgrounds to become parents’ guides and be able to provide consultation and support for the families in their respective native language. This measure aimed to inform newly arrived immigrant families about where to get support for their children, to help the entire family, and to give them confidence in their navigation of the Austrian social support system. These parents’ guides will be described in more detail in the next section.

Besides training the parents’ guides, team members explained the goals of the organization in the following manner:

We are really making sure that the support system is available, but we are also making sure that the families know…we look, that as far as possible the [existing] help is exhausted, that the support systems are working, that the families have time, maybe to start a job. We accompany them to school and kindergarten. That is, we are there, often having a mediator role, where there are different attitudes and views…

The goals of the project are thus 2-fold: to provide information and support for the caregivers for children with disabilities and to act as a mediator between the caregivers and the various systems. The team members are describing their work/concept of work similar to a family-centered approach. Due to this, the team members perceive the help they provide as a means to empower families through continuous education. The quote below illustrates this:

…to teach them competences, to give them the attitude: “I know, how to work with my children. I have knowledge. I am strong. I have competencies.” And yes, get out stronger and I think that is a solid base to participate and see the chances to participate. And we try…to lead the parents to independence…and that the parents do that themselves, to take the application to the office. Sometimes we do that ourselves, when we see that the family is overwhelmed. But in general, we do that with them, but the things they can do alone, they do alone. That is our fundamental attitude.

The team members perceive the offering of support and advice as a natural consequence of their work. Moreover, there is no limit to how often the family is supported by the project or for how long they can be supported. Responding to a question whether (and how often) families can come at a time of their choosing, a parent guide said: “Right, again and again. So, we don’t say we’re there for you for two weeks and then we’re not. They can come at any time.” This quote illustrates that it is not only the amount of time that is provided in order to support the families, but also shows what type of relationship the parents’ guides have with the families: a trusting one, in which families can reach out at any time when issues arise.

In order to better understand the support measures used by BEAM, an overview of the BEAM project itself is helpful. The BEAM project is divided into three modules.

1) Information. As the name suggests, this module provides information about the various support structures available. During this stage, different options for intervention (e.g., possible educational paths) for the child are discussed with the families. The families also receive an overview of available service providers.

2) Prevention. This occurs within the setting of the so-called “mother chats” (Mamaplausch). In these, mothers with the same language backgrounds discuss child development and the needs of children and parents. They also discuss the rights and possibilities within the Austrian education system, various social benefits, and the healthcare system. Recently, a “parent café” was developed in order to reach fathers as well. A parent guide always organizes these informal “chats” in the native language of the group. The chats are held once a month, which gives the guides enough time to prepare the topics with the BEAM team. The parents‘ guides stated that the “mother chats” are in high demand, specifically the ones held in Arabic. The groups, currently, are increasing in size, too. As one parent guide puts it, “The program that we have…has a strong impact” on the parents, and “they learn who does what, how [they] need to do this.”

3) Knowledge transfer. In this module, the core project team trains future parents’ guides—who are volunteers with different migrant backgrounds described in more detail in the next section—in various areas. As one team member described this, “we really try to empower them, enable them to acquire skills.” After the training, these guides can then forward this knowledge to their respective (language) communities.

It should be noted, however, that all interviewed team members mentioned that support is not only provided within these modules, but also whenever a particular family needs help. As one team member put it, “When the families need help, we are there.”

The Role of the Parents’ Guides

Parents’ guides, as described earlier, lead various “chats” and assist individual families in various ways. This assistance includes helping them with diverse bureaucratic processes (e.g., submission of applications for welfare benefits), the translation of important documents, the selection of kindergartens, schools, and/or employment opportunities for people with disabilities. They also accompany families to important appointments (e.g., the doctor or school enrollment). The initial step for families to be involved in the BEAM project is to personally come to the office and discuss their situation with the project team and the parents’ guide. One parents’ guide described this process in the following manner:

I have two duties: the first one to assist families, if they need something and to advise them. For example, when a family comes to BEAM…we make an appointment where the families brings all of the documentation that belongs to the children…my job starts after this first meeting, I am the bridge between the head [of BEAM] and the families. If the families have questions, they call me, and I have enough information to support them. If I can’t help, I discuss the case with my colleagues…and sometimes I accompany them to…a doctors’ appointment or…a kindergarten or school.

Certainly, parents’ guides’ ability to speak the native language of the individual family helps. “That is a huge benefit,” as one team member said, “that the project has multilingual colleagues.” However, the parents’ guides’ ability to support these families also stems from their knowledge about both systems (i.e., the home country and Austria).

…with our parents’ café, when my colleagues and boss did it, they tried to organize them und there was no interest. And since I have done it, they [the families] see a different name and say “ah, she is one of us,” and then they come…And that is always interesting when they have someone from their own country…

Another guide stated this even more clearly:

It is good when organizations…employ colleagues from different communities…we are…from…Egypt, Sudan, Turkey, Albania, China, and Indonesia, with about six or seven languages and every one of us can help the particular community…People with migrant backgrounds can help families with migrant backgrounds, more than the other [people without these backgrounds]. It is a key to the person [being helped]…

As this statement reveals, access to critical information the families require is predominately gained through the parents’ guides. Due to their shared migrant background—and shared language—the families have confidence in these guides and develop a trusting relationship. All team members stressed the importance of this common background in reaching out to the immigrant families but also for the families to be reassured that there is a person from the same cultural background that understands the specific situation these individuals find themselves in. As one parent guide explained:

…the families need help, especially the children. They know in their family they have a disabled child und don’t know where to go, but when there is someone from their own country in the company [that is, in BEAM], they are reassured. Then they know where to go, how it’s done, I think that’s great.

The parents’ guides consider their position and the BEAM project as critical to the well-being of the families. As one parent guide explained, all individuals, regardless of their background, have the right to participate and enjoy the benefits of society. This not only benefits the families, but also all of Austrian society at large, underlining the rights people with disabilities have.

…in the future…our lives [Austrian society] will be in the hands of these children. Now we have to take action, that the families are well off with their children, that they arrive in the right place and can be able to have a healthy life here…They also have the right to have a good life and to grow up in this society with all the possibilities it has to offer. And to have a healthy and good family is what every child wants. Therefore, such projects are very important so we can give the families and children the chance for a brighter future, a brighter future for all of us.

Discussion

This study explored the experiences of three refugee caregivers—originally from Syria and Iraq, but now living in Austria—with children with disabilities, using qualitative methods to discover their experiences accessing social support. The views of five service providers were also examined. Our results not only highlight the challenges these families face when accessing social support, but they also reveal a good practice example of one project that currently works at the intersection of (forced) migration and disability.

Taken together, the participants’ accounts depict numerous challenges regarding structural support. Consistent with research about immigrant families with children with disabilities who encounter language barriers when trying to access social support (e.g., Lindsay et al., 2012; King et al., 2013; Hedderich and Lescow, 2015), our findings indicate that language and communication are significant barriers for refugee caregivers. Our study reveals that issues interacting with social service providers can result in these families not gaining access to the necessary services for their children/siblings with disabilities that they are entitled to. Caregivers also had problems understanding the requirements they needed to complete before contacting service providers (e.g., the assessment of disability), and, generally, had difficulty accessing relevant information.

King et al. (2013) has identified this lack of accessible information as the biggest challenge immigrant (refugee) families face in the host country. This language barrier, in our study, was a major hurdle that obstructed the caregivers’ navigation of the entire Austrian social system. According to the study participants, a pathway to solving this issue is acquiring German-language skills through attendance of German-language courses. However, even access to these courses proved to be problematic, since childcare was not available for the caregivers, a challenge that would be particularly important to tackle to help them attend these courses. Attending language courses also proved difficult for people with disabilities, something highlighted almost 20 years ago by Roberts and Harris (2002). BEAM delivered critical help in our study: not only did they provide information as to where courses were offered, but they also offered their own language courses aimed to people with disabilities.

Scholars also often advocate for the use of interpreters to overcome these language barriers (Lindsay et al., 2012; Brassart et al., 2017; Arfa et al., 2020). Working with interpreters, however, also has drawbacks, not the least their budgetary expense. Errors in translation can be made, interpreters can be unfamiliar with the specific field, and due to this, caregivers’ may not trust them (Brassart et al., 2017). Moreover, meeting the needs of refugee populations often goes beyond simply translating information from one language to another, but requires offering culturally sensitive support (Kavukcu and Altintaş, 2019).

Here, the BEAM team, specifically the parents’ guides, proved to be of help in these situations. The individual parents’ guides acted almost, to use Hedderich and Lescows’ (2015) words, as “cultural interpreters,” or people who navigated between different systems and languages and acted as an important bridge between immigrant families and the service system. Since they come from the same country of origin as the caregivers, not only do these guides speak German and the native language of the caregivers, but they are also familiar with the systems in both countries. Due to this, they can provide adequate support to immigrant families. The caregivers perceived the guides, in particular, and the project, in general, as important aspects of instrumental and emotional support.

The caregivers seemed also to have developed a sense of trust in the parents’ guides, allowing a trusting relationship to have developed between them. This, particularly for people who have fled difficult situations in their home country, has been seen as important (Lindsay et al., 2012; King et al., 2014). This trusting relationship between parents’ guides and caregivers enabled them to feel comfortable to raise questions about different aspects at anytime, enhanced their ability to cope with challenges, and, as other scholars have noted, helped them feel more empowered (Fellin et al., 2013; King et al., 2013; Robertshaw et al., 2017). This was also described by the BEAM team members as one of the main aims of the project.

The BEAM team members also demonstrated that they engaged with the caregivers’ values, beliefs, and understanding about disability, which is an important prerequisite when working with immigrant families (Lindsay et al., 2012; King et al., 2013). This cultural sensitivity was shown in three main ways. First, the adjustment of the project’s name. Second, the training of parents’ guides to help approach immigrant families from different communities. Third, the organization of the so-called “chats,” the interactive educational programs in which mothers and fathers can meet other caregivers coming from the same country and exchange existing knowledge. Other scholars have highlighted how important this type of support is (i.e., the “chats”), as it can reduce stress and lead to a better quality of life for caregivers (Chiang, 2014). BEAM also organized these chats in the respective native language of the caregivers, which, as has been demonstrated elsewhere (Jacob, 2018), encouraged caregivers to attend. In addition to providing culturally sensitive support, however, BEAM also provided support for the whole family (i.e., not just the children with disabilities), which previous research has indicated is essential (Halfmann, 2012; King et al., 2013, 2014; Brassart et al., 2017).

Regarding the social network of the interviewed caregivers, BEAM also played a critical role. Since the caregivers had a limited network due to forced migration to Austria—and having left most relatives behind—their ability to quickly access information and receive support had been dramatically reduced. This, according to Khanlou et al. (2017) and others (e.g., Lindsay et al., 2012; King et al., 2013), can increase the burden of care, lead to social isolation, and, in the end, reduce the probability of caregivers accessing the support services they need. Our findings reveal that BEAM was the only organization that provided the necessary information that the caregivers had not received otherwise.

To conclude, this explorative study demonstrates that for caregivers to be able to successfully navigate a different social support system, a set of structural problems have to be overcome. The most prominent of these are: language barriers, knowledge barriers, and barriers to the growth of a social network. For all of these, our study has shown the critical role that parents’ guides—as “intercultural interlocutors”—can play. Service providers, in our case, clearly have a lack of knowledge and/or experience working with families with children with disabilities who are also refugees. This shows that there is still an issue of organizations not understanding how to work with these particular families. Until this is improved, the parents’ guides will continue to play an incredibly important role.

Of course, we are aware of the limitations of this study, particularly its small sample size. Moreover, all three of these families have various backgrounds and needs, and they do not represent every refugee family in Austria. However, our study showed that all three families had similar problems in accessing their needed social services and that the BEAM project was perceived as offering critical support in the area of disability and (forced) migration. Research has called for a better link between service providers working in the areas of (forced) migration and disability (e.g., Brassart et al., 2017; Robertshaw et al., 2017). Working at the intersection of these two areas, the BEAM project is taking up this call. Due to the critical support they offer caregivers, BEAM can be seen as good practice example to be modeled not only in Austria, but in different countries as well.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will not be made available by the authors for confidentiality reasons as consent for this was not obtained from the participants. The consent form states that only processed data (excerpts) will be made available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Edvina Bešić, [email protected].

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

EB and LH both substantially contributed to the article regarding the study’s design, data analysis, and interpretation of the findings. LH collected the data. EB wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partly supported by a research award from the Erzherzog-Johann- Gesellschaft—Initiativ für Kinder und Jugendliche mit Behinderung. Open access funding provided by the University College of Teacher Education Styria, Graz, Austria.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the caregivers and BEAM team members who made this research possible.

References

Arfa, S., Solvang, P. K., Berg, B., and Jahnsen, R. (2020). Disabled and immigrant, a double minority challenge: a qualitative study about the experiences of immigrant parents of children with disabilities navigating health and rehabilitation services in Norway. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20:134. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-5004-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Brassart, E., Prévost, C., Bétrisey, C., Lemieux, M., and Desmarais, C. (2017). Strategies developed by service providers to enhance treatment engagement by immigrant parents raising a child with a disability. J. Child Family Stud. 26, 1230–1244. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0646-8

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chiang, H. M. (2014). A parent education program for parents of Chinese American children with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) a pilot study. Focus Autism Dev. Disabil. 29, 88–94. doi: 10.1177/1088357613504990