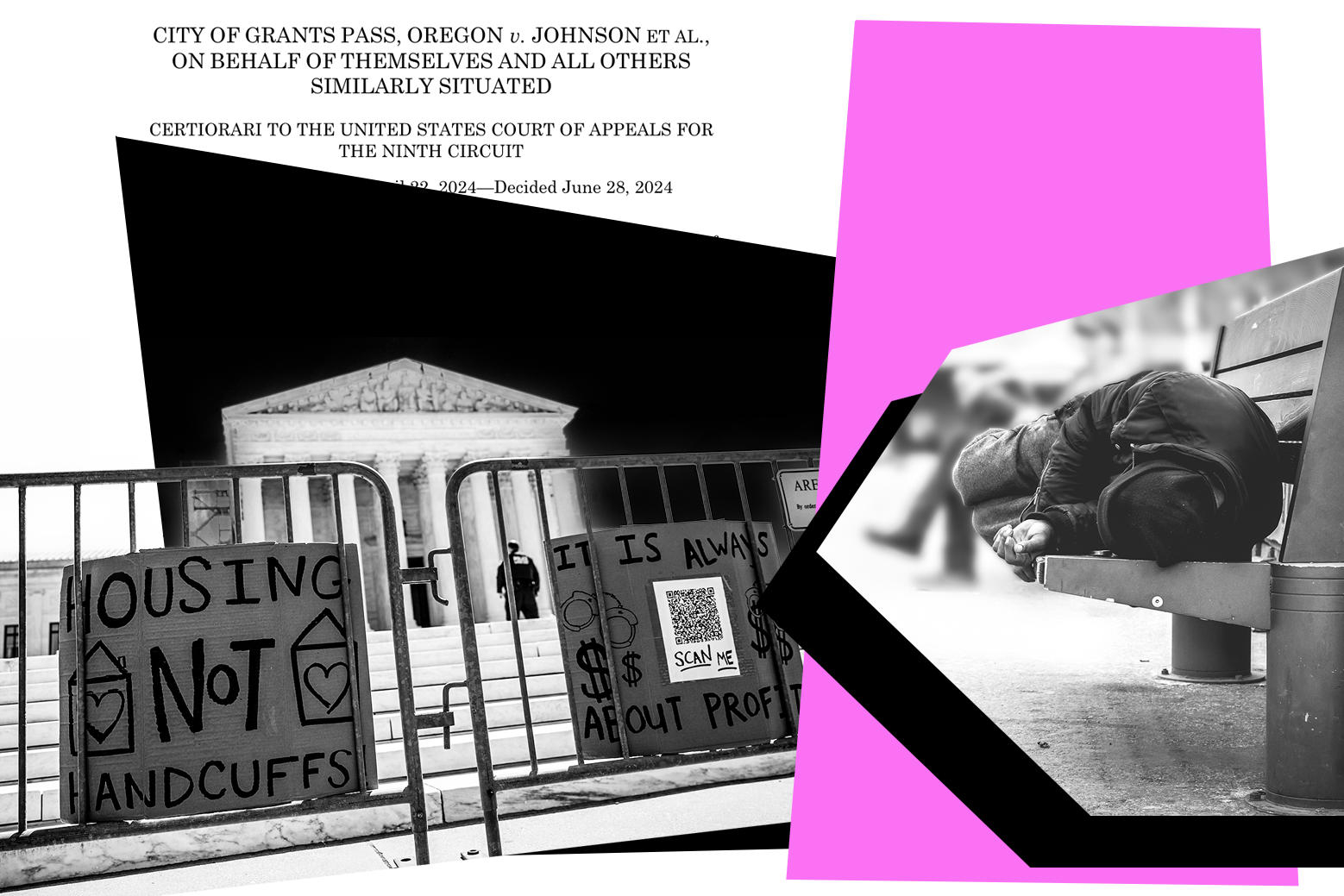

In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that homeless people can be subject to criminal and civil penalties for sleeping in public places. In City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, the Supreme Court overturned a ruling by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals that found these penalties violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. The case took place in Grants Pass, Oregon, where local politicians were trying to eradicate the homeless population through fines and prison time.

As a disability rights attorney, I know this ruling will be a devastating blow to my community. People with disabilities are disproportionately likely to become homeless. Data shows that 78% of homeless people report having a mental illness, and approximately 52% of homeless adults in shelters nationwide have a disability. People with intellectual and developmental disabilities in particular face a housing crisis due to many factors, including a severe shortage of safe, affordable, accessible, and integrated housing, as well as significant housing-related discrimination. Outdated public policies and programs unnecessarily isolate people with IDD, and community-based programs are often underfunded. Similarly, a lack of physically accessible and affordable housing pushes people with disabilities who rely on Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income into homelessness. Nationwide, only 6% of housing is wheelchair accessible.

Disabilities are at the center of the Grants Pass litigation. At the court level, several people have filed declarations with Grants Pass’s only shelter that they cannot stay in because of a qualifying disability. Carrielynn Hill, for example, could not stay in the shelter because the shelter prohibited her from using a nebulizer in her room, which she requires regularly. Debra Blake could not work because of her disability, and could not meet the shelter’s 40-hour work week requirement. Hill and Blake are examples of the impossible choices that many homeless people with disabilities face: they cannot stay in a shelter, but if they remain unhoused, they risk being prosecuted under the ordinance.

Faced with the possibility of being criminalized for not having a place to live, Hill and Blake, along with other homeless people, sued Grants Pass, believing the ordinance constituted cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. They relied on the 1962 Supreme Court case Robinson v. California, in which the Court held that the Eighth Amendment prohibits state and local governments from criminalizing conditions such as drug addiction.

In Robinson, the Court decided in part based on the understanding that the Eighth Amendment prohibits the criminalization of disability. Justice Potter Stewart, who wrote the majority opinion in Robinson, declared that “it is unlikely that any state would seek to criminalize the mentally ill, lepers, or those with venereal diseases at this point in history.” Even in the early 1960s, the Court recognized that the criminalization of disability was unconstitutional.

This was a landmark decision. From the 1860s until 1972, US cities successfully criminalized disability through so-called ugly laws. These hideous ordinances prohibited people with disabilities from being present in public places. For example, the Chicago ordinance of 1881 stated that “any person who is sick, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed to be an unsightly, offensive, or unbecoming person, may not be allowed to enter any public place, except in a public place, in which he is not allowed to enter, or … [is] “You shall not be permitted to traverse any of the public streets or other public places of this city.” Professor Susan Schweik has documented how these types of ordinances were enacted in cities across the country. Essentially, ugly laws were created to oppress people with disabilities (including “ugly” beggars). Such laws were clearly unconstitutional after Robinson because they criminalized the condition of being “sick” or “disabled” in public.

However, in Grants Pass, the Supreme Court took the Eighth Amendment back to the 19th century. Justice Neil Gorsuch, writing the majority opinion, distinguished this case from Robinson, arguing that the Grants Pass ordinance only prohibited activities such as rough sleeping, regardless of housing status. The opinion implicitly dismissed Robinson as an exception that was “incompatible with the Eighth Amendment.” [Eighth] “The Amendment’s Terms, Its Original Meaning, and Our Case Law” The brief makes no mention of disability, despite the fact that 24 disability rights groups filed an amicus brief urging the Court to consider how Grants Pass’s ordinance criminalizes people with disabilities and homelessness. My organization, Arc of the United, is a proud signatory to the brief.

Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern

This dissent is why Sonia Sotomayor is the People’s Justice.

read more

In contrast, Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent recognized the impact these ordinances have on the disability community and cited extensively to the Court’s amicus briefs. She wrote that with a lack of accessible housing, “it is not surprising that the burden of homelessness falls disproportionately on society’s most vulnerable.” Justice Sotomayor also deftly undermines the majority’s reasoning by centering the story of Hill and Blake.

Grants Pass’s ordinance criminalizes being homeless. The state of homelessness (no available housing) is defined by the punishable conduct (sleeping outdoors). The majority protests that the ordinance “does not criminalize the mere state.” That said, it does not make it a crime. … The ordinance’s purpose, language, and enforcement indicate that it targets the state, not the conduct. For those without available housing, the only way to comply with the ordinance is to leave Grants Pass altogether.

Grants Pass is one of several cases in this and past Supreme Court terms that have significant implications for disability rights, even when disability is not the central theme or even explicitly addressed. Applying this “disability perspective” to the Supreme Court is critical to understanding the broader impact these decisions have on the lives of people with disabilities across the country.

Don’t believe John Roberts. The Supreme Court made the president king. This is the (unlikely) way for the Democrats to get an attractive slate of nominees. Democrat privilege is officially out of control. The Trump immunity decision will be John Roberts’ legacy to American democracy.

In their brief, disability rights groups argue that “criminalizing the involuntary act of being homeless in a city without a place to sleep is contrary to the standards of decency of any civilized society.” But the Supreme Court’s decision in Grants Pass allows local governments to punish “the very existence of unsheltered people,” including people with disabilities, as Sotomayor writes. Sotomayor is hopeful that “in the near future, this Supreme Court will play its part in protecting the constitutional freedoms of the most vulnerable among us.” In the face of this decision, Disability Rights Lawyers will continue to fight alongside people with disabilities to ensure that the constitutional and federal promises of disability rights protection are realized to the fullest extent of the law. Even when the Supreme Court’s decision contradicts these legal guarantees, it is important that the court, and the public at large, understand what is at stake.

This is part of Opinionpalooza, Slate’s coverage of major Supreme Court decisions handed down this June. Together with Amicus, we kicked off the year by explaining how fundamentalism has engulfed the law. The best way to support our work is to join Slate Plus. (If you’re already a member, consider donating or buying some merch.)