Based on three cohorts of population-based ageing in the South of France, this study shows that there are gender differences in the time spent in poor SRH with age, but no gender differences were found for expected lifespan in good health. The proportion of UHLE in both sexes increased with age, but women had a higher TLE and UHLE at all ages, and HLE was similar to that of men. Comparing life expectancies calculated using subjective health indicators and disability indicators (considered to be more objective indicators), showed specific results for each indicator and revealed gender-specific trends across ages. In fact, UHLE was higher than DLE in younger and older adults (with larger differences in men) and lower in older adults (with larger differences in women). With regard to good SRH, the lifespan free from IADL disability was similar for both sexes. It should be noted that for both sexes, HLE was lower than DFLE at younger ages, but higher at older ages, with larger differences and earlier onset in women. Furthermore, although the proportion of DLE in TLE increased significantly with age (especially in women up to age 75 years), this trend was less significant for the proportion of UHLE in TLE, and the increase in the proportion of UHLE in TLE was slower and similar in both sexes.

Gender differences in expected years spent with poor and good sexual reproductive health

As mentioned in the introduction, the well-documented gender health and survival paradox confirms that men and women have different health profiles. Women are more likely to have higher morbidity (e.g. hypertension, depression), worse socio-economic conditions and non-fatal but disabling chronic diseases (e.g. dementia, arthritis, frailty)4,5,25,40,41,42. In contrast, men are more likely to suffer from fatal diseases (e.g. heart disease, stroke)6,43. Although we did not use multimorbidity as an indicator of health in this study, our results support this paradox and suggest that, compared to men, women can be expected to have poorer subjective health and live longer despite disabilities.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies that used SRH as a health indicator to calculate HLE and UHLE30,34,44,45. Despite differences in TLE between studies, all results indicated that women are expected to live longer with poor SRH than men30,34,44,45. Similar to our study, other studies have reported that the expected years spent with good SRH are relatively similar for men and women, while the proportion of HLE in TLE is higher in men than in women30,45. However, in contrast to our gender-specific trends in HLE and UHLE, Belon et al. found that in older Brazilians, women spend additional TLE with good SRH rather than poor SRH (e.g., at age 65, HLE 17.1 out of 19.6 years of TLE in women, compared with HLE 13.5 out of 15.6 years of TLE in men). They also found that women and men spent approximately the same amount of time in poor SRH (+ 0.4 years at age 65 and + 0.1 years at age 80+).29 Such differences between our findings and those of our study may reflect contrasting life circumstances and cultures (e.g., how do people perceive aging? What does “good or poor health” mean to them in older age? What are the gender-specific social norms?). Indeed, as mentioned above, measures of SRH also include and reflect cultural specificities.

Comparison of trends in life expectancy based on SRH and disability indicators

We found that, for both sexes, estimates calculated using disability indicators are almost systematically different from those obtained using SRH indicators, even though HE is correlated and decreases with age. This result supports the fact that SRH and disability, although moderately associated (medium effect size), are complementary health indicators for understanding and addressing individuals’ biopsychosocial status as they age. The present study makes an original contribution to the literature on HE by investigating gender-specific patterns in age trends of life expectancy in good and poor health calculated using SRH and disability indicators.

Our study highlights important age differences in trends in HE based on SRH and disability indicators. Indeed, we found an inverse pattern in trends in expected survival time for poor SRH and for disability with increasing age. Regardless of gender, expected life expectancy for poor SRH is higher than expected life expectancy for disability at the youngest ages and decreases with increasing age. There are several hypotheses that could explain these findings. First, in early old age (<70 or 75 years of age), people are more likely to report poor health even if they do not necessarily need assistance to perform activities of daily living. For example, in our analytical sample, of the 729 people aged 75 years or younger who reported poor SRH at baseline, only 109 (15%) reported difficulties with IADLs. With increasing age, we found a situation in which more people consider themselves disabled but not necessarily in poor health. Perhaps the “early old” are more critical of their health than the “extreme old.” The most elderly people consider it “normal” to experience impairments and declines in old age and report relatively good subjective health despite their disabilities. Thus, even if they have IADL disabilities, they do not consider themselves to be in poor health because they are almost as healthy as or healthier than people who are in a worse state than them (“downward social comparison”). This supports the fact that, as proposed by Jylhä M.21, SRH reflects the difference between an individual’s current state and past experiences, in comparison with their age and with people they know. Secondly, the reversal trend observed with age indicates that the presence of impairments in old age does not necessarily promote a sense of poor health. Indeed, on the one hand, it can be hypothesized that if these impairments do not prevent an individual from continuing the activities that he or she values despite old age (receiving visits from family and friends, playing cards, cooking, etc.), he or she is less likely to feel unhealthy than he or she would have been in his or her younger years. On the other hand, if there are limitations, older people may lower their criteria for good subjective health (recalibration response shift) or prioritise them (reprioritisation response shift)27. Thus, from a public health perspective, indicators of SRH and disability in older people seem to be complementary, not interchangeable. Moreover, depending on the research and health system questions, it may be appropriate to use these indicators in combination or separately. From the perspective of health care and long-term care planning, it is advisable to use indicators of disability, whereas from the perspective of monitoring the consequences of social inequalities in health, it may be more appropriate to understand the dynamics of poor subjective health indicators. Identifying people who are not yet disabled but who perceive their health to be poor can also address the associated needs to improve well-being, quality of life and reduce the risk of health deterioration.

The study also reveals gender differences in the trends of DLE and UHLE with age. In fact, DLE exceeds UHLE earlier in women than in men. This result can be explained by the fact that women seem to have a higher subjective health standard at a younger age and therefore have a higher proportion of UHLE (46% of TLE at age 65) than men (38% of TLE at age 65). As they age, women tend to revise their subjective health standard downwards, reducing the proportion of their remaining life expectancy that is devoted to poor subjective health, even though more than half of their remaining life expectancy is spent with disability from age 75 onwards. This change in subjective health standard seems to occur later in life in men.

Advantages and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate gender-specific patterns of HLE based on subjective health status and DFLE in an older population and compare the two. This shows to what extent the indicators used to assess health status affect the estimates of HE. Therefore, this study provides a unique additional contribution to HE research in older adults. Second, we used a multistate modeling analysis, which is appropriate for longitudinal data. Longitudinal data such as ours cover a relatively long period of time, and health behaviors and care environments may change, so the probability of death and the probability of having good or poor health status may also change. Therefore, it is important to emphasize that, unlike prevalence-based methods, the IMaCh program used the current incidence of all possible transitions between states (including recovery) and the dynamics of survival over time to provide a more realistic picture of TLE and HE. Third, we did not exclude participants who were institutionalized in later survey waves from the analysis because they were still being followed up.

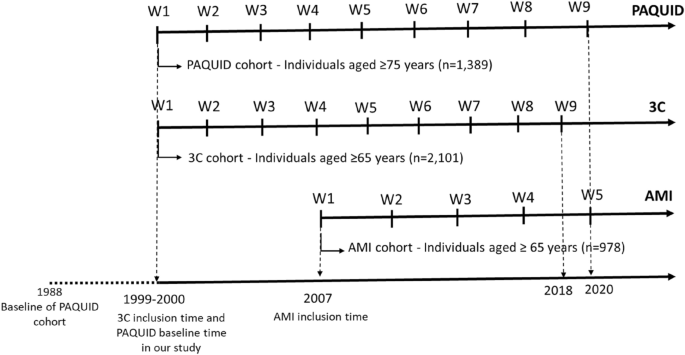

Despite these strengths, some methodological choices may have influenced our results and should be discussed. First, to define the poor SRH group, we combined individuals who self-rated their health as fair, bad, and very poor. This classification may have influenced our estimates by underestimating UHLE, since participants who self-rated their health as fair are considered relatively healthy. However, our classification is similar to that used in several studies34,35,36. Second, our sample is not representative of the general French population and, as shown in a recent study, the southern department to which Bordeaux belongs has one of the highest LEs among the 100 French departments (25th out of 100 for LE at age 60 for women and 22nd out of 100 for men)46, so our results cannot be extrapolated to the entire French population. Third, some specific patterns were found in the AMI cohort (retired agricultural workers). In contrast to the other cohorts, the DFLE was longer in women than in men, which could be explained by different selection criteria according to gender. In fact, the farmers’ health insurance reimbursement database can only include farmers who have insurance in their own name (men are more likely to be in this situation). Women who have insurance in their own name (who may have been included in the sample) may have been different from women who have insurance under their husband’s policy (who were not enrolled in the study). They are more likely to be farm owners, but therefore are not representative of all women involved in agriculture. This result differs from the results of the other two cohorts, but does not change the conclusion. However, it should be noted that by combining the three cohorts, we are trying to take into account to some extent the different profiles found in the general population (e.g. rural, urban dwellers, retired farmers, etc.). Moreover, the design of these cohorts and the definition of the two health indicators were similar, so pooling these cohorts allowed us to ensure an adequate sample size for stratification by gender and to increase the statistical power of the analysis. Fourth, since there is a gap of several years between the actual starting points of the three cohorts and the participants do not belong to the same birth generation, it is important to note that besides age, the perception of aging may have evolved from one generation to the next, which may change the importance of different factors taken into account when self-assessing health. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that there may be a cohort effect in the observed changes in the dynamics of DLE and UHLE. However, the results regarding the age of change for the pooled sample and the individual cohorts were consistent (the turning point is between 75 and 77 years depending on the cohort). Finally, the measurement of IADL disability was less objective than that obtained from performance-based tests. It is also important to highlight that although the (Lawton-validated) scale used included the assessment of three additional IADL items in women, this gender-specific assessment did not increase the likelihood of disability in women compared to men. In fact, using the same scale, it has been shown that individuals fall into IADL disability through limitations in shopping and mobility, two IADL items common to both sexes47. For women, limitations in three additional IADL items arise later. In this study, we were not interested in the number of IADL limitations participants exhibited, so the impact of this gender-specific IADL disability assessment on the results was essentially null. Our results showing that women had higher DLE than men are consistent with the extensive literature on gender differences in DLE/DFLE.