Leaf blowers are one of the most hated things in the modern world. They’re noisy, they pollute, and besides, a leafless lawn is not even that important. Many towns and cities have banned gas-powered leaf blowers, and some have strict guidelines about when and where they can be used. But in Los Angeles, California, the sound of leaf blowers has never been quieter.

Photo by Hector Alejandro. CC by 2.0

Photo by Hector Alejandro. CC by 2.0

California has banned the sale of gasoline-powered leaf blowers in 2024, but this latest move is just the latest blow in Los Angeles’ leaf blower wars, a battle that dates back decades and has stirred questions about labor rights, the environment and concepts of beauty.

They blow

In the 1970s in Los Angeles, it was common for people to hose down their driveways. Homeowners, renters, and gardeners would pour dirt, leaves, and everything else onto the roads. But a severe drought in 1976 and 1977 led many Californians to start conserving water and stop hose-down all the time.

Around that time, the Japanese company Echo introduced a product they called the Clean Up Machine. Originally invented in 1947 as a pesticide-dusting device, it seemed to solve the problem perfectly: clearing leaves and debris from yards in a drought-resistant way.

By 1989, it’s estimated that nearly one million leaf blowers had been sold in the United States. Leaf blowers were ubiquitous, yet almost universally disliked. Facing pressure from homeowners and residents of quiet residential neighborhoods throughout the 1980s, many city councils introduced or passed outright bans on leaf blowers. From the beginning, California cities were on the front lines of the fight against leaf blowers, with Beverly Hills being the most high-profile ban in Southern California.

Despite the noise and exhaust fumes, leaf blowers were also very fast at clearing leaves from yards. And for those who tend to lots of lawns, not just their own, this speed meant a lot. In 1989, Jaime Aleman left his job in office supplies to start his own landscaping company. Landscapers often get their start by being introduced to a few homes, or customers, by older gardeners. Throughout most of the 20th century, many of the gardeners in Los Angeles were of Japanese descent. But in the ’80s and ’90s, the landscape began to shift to mostly Latin American gardeners. Their clientele became known as La Ruta (the Root).

More leaf blowers = more revenue

For a landscaper, the difference between failure and success is speed. Landscapers get paid per lawn, but profits are small to begin with. Using a blower instead of a rake allows them to cover a larger area of lawn in a day. But as Alemán got started and expanded La Ruta, tensions had been building for nearly a decade. Rumors began circulating in the area that the Los Angeles City Council was seriously considering banning gasoline-powered blowers. Jamie saw the proposed ban as a clear threat to his fledgling business, and he began asking around for advice on how to fight back.

Photo by Marc Falardeau. CC by 2.0

Photo by Marc Falardeau. CC by 2.0

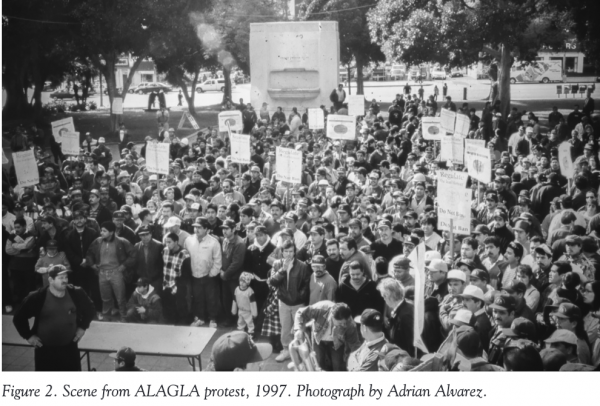

Dr. Alvaro Huerta, now an associate professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, was a young Chicano activist from Boyle Heights in 1996. He had a small group of activist friends working on some big issues, like getting UCLA to provide financial aid to undocumented students. Huerta agreed to help Jaime, and together with his small group of friends and activists, he took action. The Association of Latino Gardeners of Los Angeles (ALAGLA) was born. ALAGLA’s opponents were no small foe. It looked like a citywide ban would soon be passed into law.

But the City Council didn’t think about who was on the other side of these blowers: people like Jaime Aleman. As a landscape gardener, Aleman was understandably uneasy about the policing of the tools she uses every day. ALAGLA saw their best chance at tipping public opinion and began planning protests to grab press attention. As national and international press reported on the gardener protests, the public perception of blowers in Los Angeles became a bit more complicated.

Gardeners, on the other hand, delivered a powerful and simple message: the ban would make it harder for them to make a living. The room erupted in applause whenever someone spoke in defense of the gardeners. Ultimately, the City Council rejected the alternative motion and decided to vote for the one-line ordinance instead. When they brought up the ban on gasoline-powered leaf blowers, it passed easily by a vote of 10 to 3. Soon, it was illegal to use a gasoline-powered leaf blower in the city of Los Angeles.

Crime and Punishment

If found in violation of the ordinance, gardeners could be fined $1,000 and jailed for up to six months. This seemed like cruel and unusual punishment to many, especially the gardeners themselves, and threatened their livelihoods. For a time, they chose to ignore the ordinance en masse. Gardeners continued to use gasoline-powered leaf blowers in defiance of the new ban. Then, in January 1998, when the law was about to be fully implemented, ALAGLA staged a hunger strike, trying to delay, if not stop, the implementation of the new law altogether.

The hunger strike began on January 3, 1998. Many, including the organizers, camped out on the front lawn and slept in front of City Hall. After a few days, four men became dangerously weak and dropped out at the request of their doctors. But the remaining seven hunger strikers held out for another seven days, until Friday. Finally, several city council members and Mayor Riordan promised in writing to negotiate with the gardeners. They voted to reduce the penalties, although they probably wouldn’t stop the enforcement. It wasn’t the crushing victory ALAGLA had hoped for, but it was enough for the gardeners to end the hunger strike and go home.

Public opinion shifted, but the ban on gasoline-powered leaf blowers became law. After the ordinance with reduced fines was fully implemented, Huerta and the remaining members of ALAGLA hatched one last plan. Because the law specifically banned gasoline-powered blowers, some gardeners switched to methanol-powered blowers to get around the law. These modified methanol-powered blowers are just as noisy and polluting, but technically legal. But because it’s difficult to even tell if a blower is methanol-powered and not gasoline-powered, law enforcement stopped enforcing the ban altogether.

The war continues

In the end, the blower ban was ineffective and the police decided not to enforce the law. The gardeners lost the battle at city hall, but ultimately won a quiet victory: the ban was passed, but with no real enforcement, the gardeners continued to use their blowers.

The leaf blower wars have been in the shadows for a while, but in 2024, nearly 30 years after the ALAGLA hunger strike, they’re flaring up again. And this time, gasoline-powered leaf blowers may actually be on the way out. Lawn mowers have surpassed cars and small trucks as a leading source of pollution, according to Michael Cacciotti, vice president of the South Coast Air Quality Management District.

There’s evidence that sustained exposure to that level of noise can cause significant hearing damage, plus emissions are severe because they don’t have catalytic converters to break down pollutants and reduce smog.But battery technology and electric leaf blowers have come a long way in the past 30 years, and the battle today is mainly about getting people to switch to electric.

Noise levels of a gasoline-powered leaf blower using the NIOSH Sound Level Meter app. Photo by Chuck Kardous.

Noise levels of a gasoline-powered leaf blower using the NIOSH Sound Level Meter app. Photo by Chuck Kardous.

This time around, the government offered subsidies to encourage gardeners to make the switch, and some local governments have tried in good faith to cooperate. But the reality is that electric blowers are, at best, an imperfect replacement. Of the three main objections to blowers — noise, dust and emissions — going electric only really solves the third problem.

During the fight in the 1990s, representatives of blower manufacturers promised quieter and cleaner machines, but as several city council members pointed out at the meeting, the promise of quieter blowers never came true. The statewide ban seems aimed at forcing manufacturers to come up with a better solution. One idea is to involve gardeners in the political and design process so they aren’t penalized for doing the job they were hired to do, and in the meantime, to ask themselves whether a beautiful garden is a leafless garden or a quiet garden.