This article is part of “Overlooked,” a series of obituaries about notable people who went unreported in The Times since 1851.

During New York City’s Gay Pride weekend in 1984, Dennis Katz heard his doorbell ring and was surprised to open the door to find Lorenza Bottner, a transgender artist, standing there in a wedding dress that had been custom made to fit her armless body.

“I’m here to party!” Ms. Böttner said in her mixed German-Chilean accent. Ms. Böttner rang the wrong apartment, but Mr. Katz let her in anyway. “From that moment on, we were never apart,” she said.

It was pure coincidence that Katz worked in an art supply store and Bettner was a prolific artist.

Throughout her life, Böttner created a wide range of works using her feet and mouth in painting, drawing, photography, dance, and performance art. She produced hundreds of paintings in Europe and the United States, and danced in public on large canvases while making impressionist brushstrokes with her feet. In New York, she performed in front of St. Mark’s Church on the Bowery, where her future roommate, Katz, provided her with large sheets of paper and other props.

Although Böttner did not achieve mainstream fame during her lifetime, her work, which critiques both gender norms and concepts of disability, in recent years has been recognized as an important contribution to the art historical canon, in part due to her radical representations of atypical bodies.

Boettner’s work received further attention through the traveling exhibition “Requiem for the Norm,” organized by transgender writer and philosopher Paul B. Preciado.

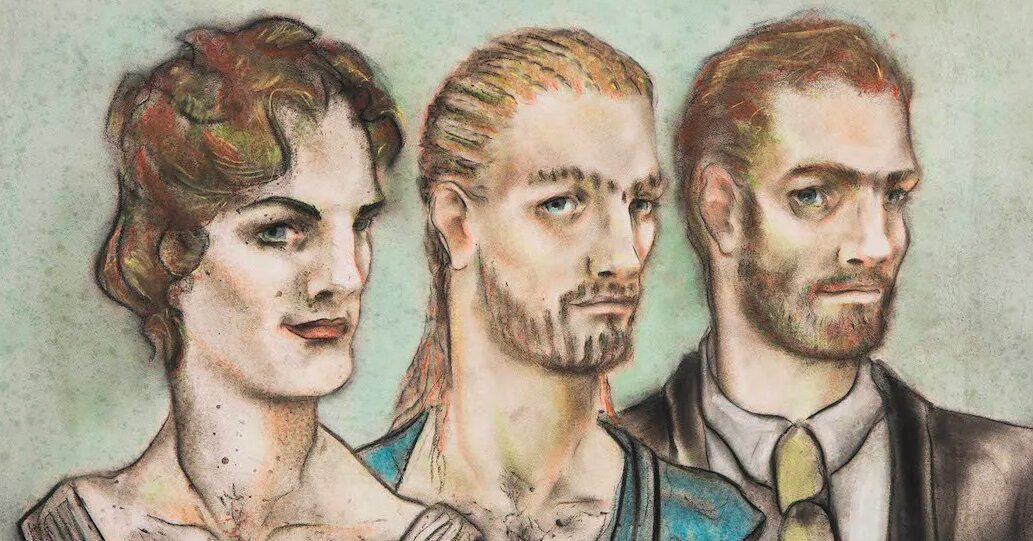

In her self-portraits, Böttner celebrated and eroticized her appearance, portraying herself as a gender-diverse version of herself, and in a photo series called “Face Art,” she used make-up to undergo a process of transformation with masks that accentuated or distorted some of her features.

Böttner also replaced his own face and body with archetypal depictions of women from art history, such as a ballerina or a mother nursing her child. In one work, “Venus de Milo,” Böttner’s body was cast and transformed into a sculpture that imitated a famous Greek statue.

“I wanted to convey the beauty of a disabled body,” she said in Lorenza: Portrait of an Artist (1991), a short documentary about her life. “I have seen so many statues that are admired for their beauty, and they too have lost their arms in accidents, but they have lost none of their aesthetic appeal.”

Lorenza Bettner was born to German immigrants in Punta Arenas, southern Chile, on March 6, 1959, and was identified as male at birth. She was a precocious child, displaying an early talent for art and a love of birds.

When she was about nine years old, she climbed an electricity tower hoping to find a nest and find a baby bird to keep as a pet. The mother bird suddenly spread her wings, startling her, and Lorenza lost her balance and grabbed onto the live electric wires hanging around her to avoid falling. Both of her arms were severely burned up to the elbows and eventually had to be amputated at the shoulders.

In 1969, she emigrated to Germany with her mother, Irene Bettner, who worked a variety of jobs, including as a baker and a house cleaner. Lorenza received treatment at the Heidelberg Rehabilitation Center and received her education at the Lichtenau Orthopedic Rehabilitation Clinic, according to Preciado. She struggled to recover and refused to use a prosthetic arm, despite doctors’ disappointment.

“During her teenage years, Lorenza became depressed and apathetic and probably attempted suicide more than once,” Katz said in an interview. “It was her mother, Eileen, who put the pen in her mouth and instilled in her the will to live through art.”

From 1978 to 1984, Böttner studied fine arts at the University of Kassel, where self-portrait became the basis of her artistic practice. During her studies, her interest in performance developed and she developed a hybrid form of expression that she called “dancing paintings” (“tanz malerei” in German) or “pantomime paintings” (“pantomime malerei”).

After graduating in 1984, Boettner moved to New York and studied dance and performance at New York University on a grant from the Disabled Artists Network. She frequented nightclubs and roller rinks and was a beloved presence in New York’s queer artistic circles.

“This is the guy who had the phone numbers of William Burroughs and Andy Warhol,” Preciado said.

Boettner also posed for photographers Joel Peter Witkin and Robert Mapplethorpe, but felt that their images exploited her disability, a dehumanizing gaze that Boettner sought to invert and deconstruct in her self-portraits, which celebrated her own beauty and humanity.

“If medical discourses and representations aim to desexualize and degender disabled bodies, Lorenza’s performance work eroticizes the armless trans body, endowing it with both sexual and political power,” Preciado wrote in an exhibition text for documenta art fair, where she first showed the work in 2017.

Curator Stamatina Gregory, who will show “Requiem for the Gnome” at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in Manhattan in 2022, said the outpouring of support from Boettner’s past friends, lovers, colleagues and acquaintances has been overwhelming. “I had no idea how significant putting on this exhibition would be in expanding the study of Lorenza’s life and work,” Gregory said in an interview. “Her time in New York was incredibly formative in terms of experimenting in her studio and building her community.”

According to Katz, she “became more comfortable as an artist and started using more color.”

Bettner learned she was HIV positive in 1985. The debilitating effects of the disease made it difficult for her to travel or work toward the end of her life, which she spent mainly in Germany and Spain.

She died of AIDS-related complications in Munich on January 13, 1994, aged 34.

Preciado came across Bettner’s work while researching the 1992 Paralympic Games in Barcelona in 2008, where Bettner served as a source of inspiration and embodiment of the armless mascot “Petra.” Preciado wanted to learn more about Bettner, but had difficulty finding any information about her beyond where she was educated.

When Preciado was appointed curator of documenta 14 in Kassel, where Böttner studied art, in 2015, it felt like divine intervention: “I’m not a religious person, and I don’t believe in the paranormal,” he says, “but something in me just told me I had to find Lorenza.”

Preciado tracked down Bottner’s mother and soon showed up on her doorstep. “Irene asked me why I was looking for Lorenza,” he says. “I said, ‘Yes, I’m transgender, just like Lorenza.’ We hugged, and she said, ‘I’ve been waiting for you for 20 years.'”

Her mother shared with him hundreds of Boettner’s artworks, as well as many personal items that she had kept.

“I always believed in Lorenza’s art and knew it would be popular,” Irene Boettner said in a phone interview. “I still believe it will be even more popular.”

Preciado, who debuted “Requiem for the Norm” at Barcelona’s La Virreina Image Center in 2018, said he found Böttner’s work “full of hope, transformation and liberation.”

“This is not a work about transgender people or people with disabilities being victims of the system,” he said. “This is a very politically charged work that needs to be acknowledged and passed on to new generations.”