Charles Kingly was a widower and single father of four children living in the Northern Liberties neighborhood of Philadelphia in 1829. He worked in a brewery but struggled to care for his youngest son, William, who was about five years old and nearly blind.

Barbara Syon, a 74-year-old woman from Southwark, was recorded by social services as “elderly, infirm and in foster care”.

In order to stay in their homes and care for their loved ones, Philadelphia residents sought financial assistance through the Patrons of the Poor, elected government officials who administered local welfare programs. But in the 1810s and 1820s, these pensions began to be questioned in Philadelphia. Did families like the Kingleys and Zion really deserve assistance, or was it a false one?

As a scholar of early American history, a historian of disability, and a person with a disability, I am attuned to discussions of disability from the founding of the United States to the present day. While researching the daily lives of disabled people in Philadelphia in the early 1800s, I discovered records of the Patron of the Poor in the Philadelphia City Archives.

My research, published in the Spring 2024 issue of the Journal of the Early Republic, explores how and why Guardians of the Poor, along with other welfare reformers, began to ration care and outlaw pensions.

Patron of the poor

In the early 1800s, Philadelphia, like most early American cities, was a diverse welfare state.

The Guardians of the Poor levied a poor tax on each household. They used this money to buy firewood, food, clothing, and other necessities for the poor, and also provided weekly pensions to needy families.

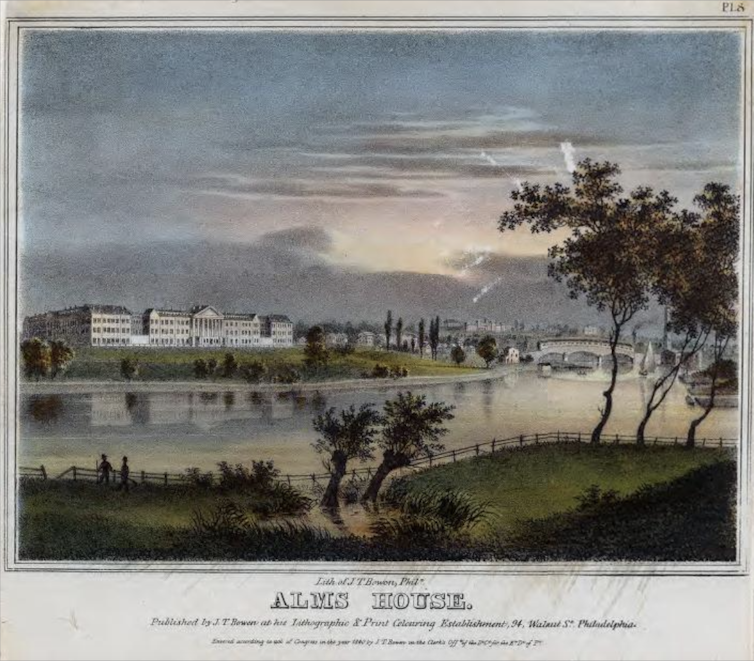

They also supported public institutions such as the Philadelphia Almshouse, which provided shelter and basic needs for the city’s poorest people, and purchased space in the Pennsylvania Hospital, where they referred the poor to medical care.

Although workhouses and hospitals were important places of treatment, many disabled families relied on pension schemes. Pensioners could be looked after in their own home by doctors employed by the Patron of the Poor. The supplementary income enabled them to continue working and to live independently.

Overcrowding at the original Brockley workhouse led officials to open a new facility on the west bank of the Schuylkill River in 1833. John T. Bowen / Library of Congress / World Digital Library

Growing poverty, deepening resentment

Like most East Coast cities in the early 1800s, Philadelphia was home to thousands of immigrants and a growing free black community. It also experienced rising unemployment and vagrancy rates, debts from the War of 1812 with Britain, and inflation due to the Panic of 1819.

As more people fell into poverty, more turned to local welfare authorities for help.

Meanwhile, taxpayers lamented the rising costs of welfare, especially the pension system. If the government was just handing out money, they asked, why would anyone work? Were people really unable to work, or were they just scamming the guardians of the poor? There was a widespread feeling that con men were eating away at the public finances.

In 1817, a citizens group called the Pennsylvania Association for Promoting Public Economy began to investigate the system. They sent questionnaires to charity organizations and government officials, asking, “What do the poor allege to be the cause of their poverty?”

Charities and authorities reported: “In most cases, a lack of employment is cited as the cause…”[A]This may be temporarily effective, but laziness, lack of self-control, and disease are most often the real causes.”

The Citizens’ Commission report concluded that “people of color, the lower classes of Irish immigrants, and intemperate day laborers” were wasting taxpayer money.

An 1817 report cited alcohol as the main cause of poverty in Philadelphia.

While the commission occasionally highlighted the gender pay gap, the rising cost of living, and other practical challenges, it focused above all on individual behavior and individual choices. The authors believed that poor people spent their money recklessly: they gambled, employed sex workers, and consumed alcohol to drive themselves into poverty.

The report triggered a series of further investigations: in 1821 a Provincial Commission was established to investigate the Poor Law, and in 1827 the National Association of Poor Patrons published the results of its own investigation.

They all repeated the same argument: the wrong people are on welfare.

Huge workhouse

To cure these social ills, Citizens’ Committees proposed abolishing pensions and institutionalizing the poor. Reformers argued that it would be much cheaper to house the poor together and feed, clothe, and shelter them on a large scale.

In Philadelphia, that meant shifting taxes on the poor to create the Brockley Workhouse, a 3,000-bed institution that served as a workhouse, orphanage, hospital, and almshouse on the west bank of the Schuylkill River, at the time on the outskirts of the city, far from the families and communities of most of the residents.

In 1902, the facility was renamed Philadelphia General Hospital. It closed in 1977 and was demolished soon after. Today, the site is home to a variety of facilities owned by the PGH Development Company.

As the manuscript collection of the “Guardian of the Poor” held at the Philadelphia City Archives reveals, Brockley Workhouse allegedly employed medical professionals to screen admitted patients and weed out welfare fraudsters from those who deserved care.

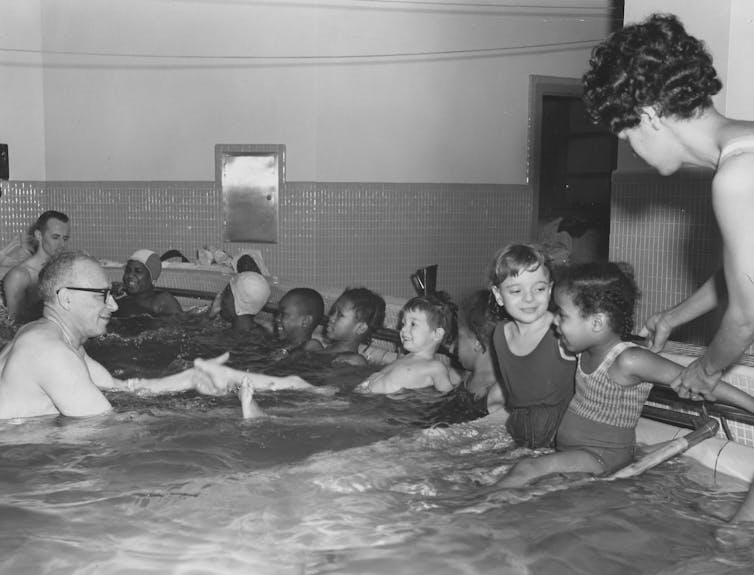

The sick and injured were sent to the hospital’s wards, where they met with doctors and medical students. University of Pennsylvania students had completed their clinical training in the workhouse, learning how to perform surgery, dispense medicines, and diagnose patients.

The poor, both disabled and able-bodied, were sent to the workhouse where they were employed in such tasks as plucking oak (unravelling rope into its individual fibres), winding thread, sewing clothes, making shoes etc. Everything they produced was sold in the local market to help fund the institution.

Reformers assumed that most people would find the workhouse conditions so unpleasant that they would leave and find work in the city instead.

A physical therapist and a polio patient in the swimming pool at Philadelphia General Hospital, located on the former site of the Brockley workhouse, in 1963. Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

The so-called scammer

It is difficult to imagine what the workhouse could provide for families like the Kingleys and Syon, who are just two of the 656 families listed in the 1829 Register of Almshouses kept by the Patron of the Poor.

When the register was transcribed, it turned out that all 656 households on the pension roll were home to single parents raising children, elderly people, people with disabilities, or some combination of these, and most of them had been living in the city for decades.

Ironically, Brockley never made a profit; Philadelphians continued to fund the facility through their tax dollars, but it never broke even.

Of course, the real costs were borne by those who were forcibly institutionalized, segregated into wards based on gender or health, and separated from their families by the width of the river.

Many people lived in extreme poverty to escape the institutions: in 1830, Matthew Carey, a prominent Philadelphia economist, argued that hundreds of Philadelphians deserved pensions because they had “gradually descended into such extreme distress and misery that any virtuous man would shudder at the sight of an inmate in a workhouse, and would, indeed, rather die than go there.”

The shift in welfare law that defunded pensions and instead funneled money to public institutions acted as a net to trap and punish the economically dependent. Welfare reformers could have looked at employers, corporations, rents, and other systemic causes of poverty. Instead, they focused on supposed con artists who didn’t really exist.