(Nairobi) – People with disabilities and older people in South Sudan face greater risks of being caught in fighting and greater challenges in getting necessary humanitarian assistance, Human Rights Watch said today.

One year after the adoption, at the Istanbul Humanitarian Forum, of the Charter on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action, the United Nations and aid organizations should do more to accommodate the specific needs of people with disabilities and older people as they respond to the wider crisis and famine in South Sudan.

“People with disabilities and older people are often left behind during attacks and find themselves at much greater risk of starvation or abuse,” said Shantha Rau Barriga, disability rights director at Human Rights Watch. “This problem is especially acute in South Sudan, where decades of civil war has increased the number of people with disabilities, and where armed forces on both sides target civilians with impunity.”

In February and March 2017, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 45 people with disabilities and older people in displacement sites in Juba and Malakal, as well as in Panyijar county in the former Unity state, where the UN declared famine in two counties in February. Human Rights Watch also met with aid organizations and the South Sudan Human Rights Commission.

Play Video

The current conflict began in South Sudan on December 15, 2013, when forces loyal to President Salva Kiir – a Dinka – clashed in the capital, Juba, with those of his then-vice president, Riek Machar – a Nuer. People with disabilities and older people have been targeted and abused by the warring parties, often because of their inability to flee ahead of attacks.

Throughout the conflict, Human Rights Watch has documented numerous cases of people with disabilities and older people being shot, hacked to death, or burned alive in their houses by the belligerents.

An older woman, recently displaced with her family from Mayendit to Panyijar county in the former Unity state, said that no civilians were off-limits in the attacks on her village: “The first time the government soldiers and militias came to my village in 2015, the old men and women who could not run were killed,” she told Human Rights Watch. “There was Gatpan Mut, for example, who was a little old, and Gatkui Jich, who couldn’t move, and many, many more whose names I can’t remember.”

During attacks in 2016 on Protection of Civilians (PoC) sites for displaced people inside of UN bases in Malakal and Juba, people with disabilities and older people were also left behind and struggled to find spaces to hide from attackers.

During a brutal attack by government forces on the Malakal PoC site in February 2016, three members of the same family with disabilities burned to death.

“When the fighting broke out, we fled to the UN compound and we left my mother and brother-in-law behind because they couldn’t walk and we couldn’t carry them,” a 45-year-old Nuer woman said. “The son of my brother-in-law, who had a mental health condition, would not leave his father behind so they all burned together in the fire.”

People with disabilities and older people who managed to flee violence have often faced problems getting crucial humanitarian assistance that other people don’t – from using latrines to accessing food distributions. People with limited mobility may not be able to reach aid hubs far from their displacement camps and cannot always rely on family or friends to carry them there.

“My children are not on the island and sometimes there are people who abandon their older relatives because we cannot offer them anything in return,” said an 80-year-old father of three children with lower body paralysis and no mobility device. “Now that I have been registered for the food distributions, I don’t know how I can access it unless I have someone to carry it for me because I have to crawl everywhere I go.”

With many aid programs focused on the UN PoC sites where more than 200,000 people have taken shelter, millions of other vulnerable civilians are effectively cut off from similar levels of support.

Aid groups, struggling to meet the needs of about 1.9 million South Sudanese displaced internally across the country as a result of the conflict and hunger, also face serious problems with security and access. Government and opposition soldiers have looted aid supplies, attacked staff, and obstructed access. To fulfil their missions, aid organizations should do more to ensure that they are meeting the needs of people with disabilities and older people, Human Rights Watch said.

Aid workers and donors should ensure that people with disabilities have access to humanitarian services on an equal basis as those without disabilities and that discrimination does not arise as a result of failing to make adequate provision for the needs of people with disabilities in their programming and distribution of assistance. They should ensure the participation of people with disabilities and older people in the design of their programs and develop strategies and action plans that eliminate physical, communication and attitudinal barriers to inclusion.

Humanitarian aid workers in South Sudan already do a lot with very little, but the needs of people with disabilities and older people – too often overlooked – need to be better integrated in their planning.

“The struggle for survival by people with disabilities and older people in the South Sudan conflict underscores just how devastating the abuses against civilians have been,” Rau Barriga said. “Humanitarian groups need to provide those who have managed to flee with life-saving assistance.”

A relative pushes John Biel Dup’s wheelchair through the dirt paths of Protection of Civilians Camp 3 in Juba,. The uneven paths make it difficult for people with physical disabilities to move around the camps..

© 2017 Joe Van Eeckhout for Human Rights Watch

Nyayak Olo Bapit, a Shilluk woman from Malakal, pictured in Juba. She was forced to flee Malakal after a bullet struck her left thigh during fighting there in January 2014.

© 2017 Joe Van Eeckhout for Human Rights Watch

Angelina Nyanhial lost her leg after it was struck by a bullet during an attack on a Protection of Civilians 3 site in Bor, in 2014. Since, she’s been living in the Juba Protection of Civilians 3, struggling to generate enough income to put her children at school.

© 2017 Joe Van Eeckhout for Human Rights Watch

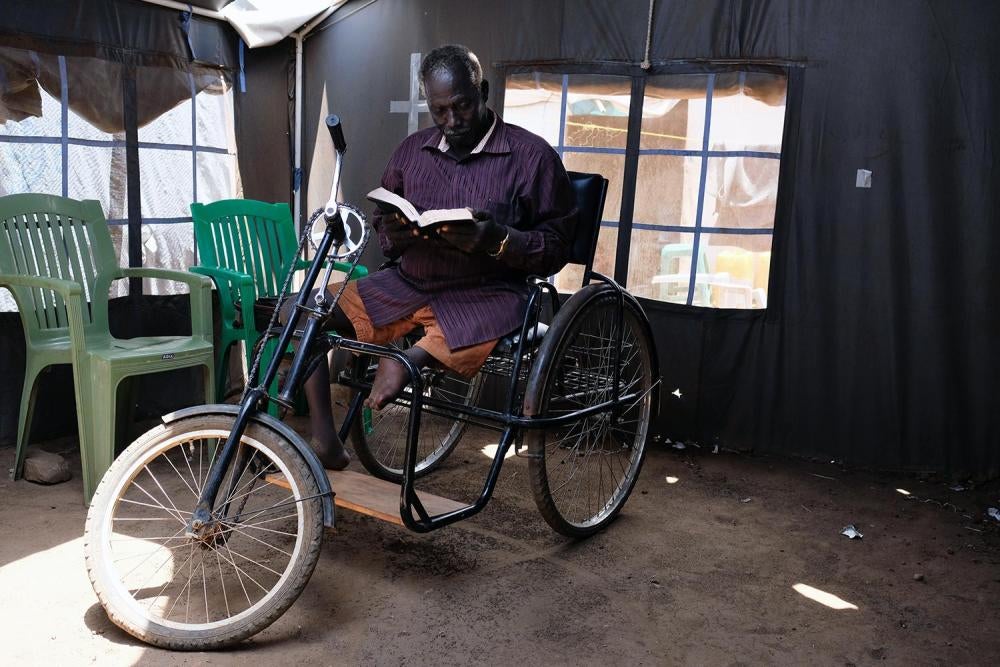

John Biel Dup, a former civil servant from Nassir, reads a book in the Juba Protection of Civilians 3.

© 2017 Joe Van Eeckhout for Human Rights Watch

Latrines without seats or hand rails are difficult to access for people with physical disabilities, who sometimes have to crawl their way into the latrines, which can be filthy. Juba Protection of Civilians 3, March 2017

© 2017 Joe Van Eeckhout for Human Rights Watch

The South Sudan Conflict

The current South Sudan civil war began as a political conflict between President Salva Kiir and his then-Vice President Riek Machar in December 2013. The fighting between forces loyal to the two men started in Juba and quickly spread to major towns north, some of which have changed hands multiple times. A power sharing agreement, signed between the two parties in August 2015, failed to end the fighting, including clashes and attacks on civilians in Juba in July 2016, and the government’s abusive counter-insurgencies elsewhere.

Both sides have committed abuses that may qualify as war crimes and crimes against humanity, including looting, indiscriminate attacks on civilians and the destruction of civilian property, arbitrary arrests and detention, beatings and torture, enforced disappearances, rape and gang rape, extrajudicial executions, and killings.

The war and abuses have created a devastating humanitarian situation. South Sudan has produced more than 1.7 million refugees, and 1.9 million South Sudanese are internally displaced. Famine was declared on February 20 in Leer and Mayendit counties, in the former Unity state, with high levels of food insecurity in the rest of the country. One hundred thousand people are starving, and about a million South Sudanese face the risk of famine. Roughly half of the country’s population needs food assistance.

An estimated 250,000 people with disabilities live in displacement camps in South Sudan according to the World Health Organization and Light of the World, an aid group. With global estimates that 15 percent of the world’s population lives with disabilities, there may be more than 1.2 million people with disabilities in South Sudan.

Legacy of Conflict, Inadequate Care

The current civil war and South Sudan’s long history of conflict between the Sudanese army and the southern Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A), have caused disabilities among large numbers of civilians, with maiming and amputations, damaged or destroyed sight and hearing, or other impairments. More than 70 percent of amputations performed by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in South Sudan result from conflict-related wounds.

The conflicts have also traumatized thousands. While there are no statistics about the number of people with mental health conditions as a result of war, Amnesty International reported in 2016 that the Health Ministry’s director of mental health had recognized an increase in the number of cases of trauma since the new war began.

Before and after the country’s 2011 independence, South Sudanese authorities have had limited capacity to respond to the medical, educational and mobility needs of people with disabilities. “No one has ever consistently pressured the government to respond to their needs,” said the interim head of the South Sudanese Human Rights Commission. “Politicians with a military background are used to seeing war amputees and the general thinking is that this is normal.”

Many of the people with disabilities interviewed had never or rarely seen a doctor. Other than those with injuries, the overwhelming majority didn’t know what had caused their disability. Chronic underdevelopment and lack of medical services have contributed to the emergence of physical and sensory disabilities linked to preventable or untreated conditions, such as polio, tuberculosis, cataracts, or other tropical diseases.

Aside from limited psychosocial, or mental health, and psychiatric services provided largely by foreign organizations, South Sudan’s capacity to respond to the needs of people with mental health conditions are also extremely limited. In 2012, Human Rights Watch found that authorities frequently detained people with mental health conditions for prolonged periods of time, in violation of national legislation and international human rights law.

Attacks on People with Disabilities, Older People

Since the beginning of the war, Human Rights Watch researchers have documented cases of people with disabilities and older people killed by government or opposition forces as they struggled to flee attacks, or because they were left behind.

In late December 2015, for example, government forces killed at least two people with disabilities and an older woman in the villages of Khorkanda and Gomba, during a string of attacks on areas under rebel control south of Wau, in the former state of Western Bahr el-Ghazal.

“The soldiers came shooting in the village around midday,” a man from the Khorkanda village, south of Wau, told researchers in April 2016. “We tried to flee and left my grandmother behind. She was very, very old. We ran to save our lives and did not pay attention to her. When the situation calmed down in the evening, we returned to the village and saw that she had been beaten to death under a tree. Her head was crushed.”

An older man said he fled his home in Mayendit county after receiving information that older people had been burned in a neighboring village in 2015. “The government forces rounded up the older people in one house and they burned the hut, so I couldn’t wait for this to happen to me too and I left,” he said.

Many of those interviewed said that soldiers made no distinction between legitimate targets and civilians, including children, women, people with disabilities, and older people. Some felt conflict has shattered many of the traditional power dynamics and cultural norms that previously governed the attitude of combatants toward civilians in South Sudan.

“Before this war, your enemies would say: ‘Disabled people are created by God so we cannot kill them, and women and children cannot be reached by the war,’” a 60-year-old former government worker with a severe mobility disability told Human Rights Watch in Juba. “But now they want to kill all the Nuer.”

Fleeing Violence

For people with physical disabilities, fleeing attacks is often much more difficult.

For example, a 51-year-old Nuer mother of seven with a physical disability and no mobility device had to make her way to the United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS) alone after the fighting began in Juba on December 15, 2013, when thousands of ethnic Nuer fled to the UNMISS base for safety. “Because my legs were paralyzed, all I could do was to crawl the whole way from home to UNMISS,” she said. “It took me five hours. Whenever I would see soldiers, I would try to hide myself the best I could.”

Many had to rely on relatives, when they could, to carry or guide them to escape attacks.

“When Nyal was attacked in May 2015, my daughter helped me get out of our house and we ran to the river,” a 70-year-old blind woman said. “It was so deep that if you knew how to swim, you could. Since I could not see her, I would follow her only by the sound of splashes in the water. It was very dangerous, but since the enemy was near, what could we do?”

Those who helped people with disabilities were also more vulnerable as they carried or guided their loved ones to safety.

A 49-year-old mother of nine with a physical disability said that she was in the town of Bentiu, in the former Unity state, when the conflict began in 2013:

I was not able to run so two people carried me into the bush with them. One of them was my cousin, Gawar Tap Liep. As we ran, soldiers shot at us. A bullet struck him as he was carrying me. We both fell down. The soldiers were coming after us so my husband and other men took him into the tall grass to hide him and we ran further. When we returned at night, Gawar was dead.

Another woman with a physical disability from Panyijar county said that her father was killed by government-allied militias during the 2015 offensive on Unity state as he carried her to safety away from Mayendit:

We were on our way to Bur when we met the government militiamen. They shot randomly at us and a bullet hit my father as he carried me. We both fell to the ground. When the attackers reached up to us, they took all of our things and beat my mother, who was pregnant at the time.

At times, the treacherous journeys to safety have themselves caused injuries or diseases leading to disabilities, as families often need to walk for days through the bushes or swamps, which can be dangerous because of wildlife and mosquito- or water-borne diseases.

An 8-year-old boy fell sick and developed a physical disability while fleeing his village through the swamps with his family following an attack. His mother said:

We stopped on an island on our way south. At night, he had a high fever and shivers. The next day, he could not move his legs. We had to carry him on our backs. When we arrived to Panyijar, the people at the primary health care unit told us that it was because of tuberculosis. They gave him tablets. We don’t know if he will be able to walk again.

“I cannot move the way my brothers and sisters do,” the boy said. “It’s bothering me. When I go to bed, I feel sad because I cannot play with them now.”

The experience of fleeing violence has also contributed to trauma for numerous civilians.

A father of three children in the Juba displaced people’s site said that one of his daughters became traumatized after seeing the dead bodies of her aunt and cousins in December 2013 as they fled to the UNMISS base in Juba:

Before the war, she was OK. But then, she started to insult everyone and run away from home for many days at a time. At the hospital, they didn’t know what she has but they gave her Phenorbitone (used to treat anxiety problems). Now, she can’t even go to school here in the PoC. Otherwise she gets into fights with other children or just runs away, and there is no fence around the school to keep her in there.

Left Behind

Many people with disabilities and older people interviewed said that relatives managed to take them to safety at the time of an attack. But not everyone was so lucky. Some told their relatives and neighbors to go ahead, fearing that the presence of the person with a disability would slow the others. Others were simply abandoned.

An aid worker who provided services to people with disabilities in the Malakal PoC site at the time of the February 2016 attack on the camp, said that at least five people her organization had been helping were killed during the attack. “One of them was a Darfuri,” she said. “He was paralyzed and his family left him behind as they fled into town with the Dinka. His shelter caught on fire and he burned alive.”

Three days after the attack, when the situation became calm enough to re-enter the PoC site, aid workers found 12 Dinka civilians with disabilities or older people who had been left behind by their relatives when they fled back into Malakal town. No one had attacked them, but they had received no water or food during that period. They were later taken to Malakal town to join their families.

One of them was an older, blind Dinka woman with a physical disability. “All the Dinka fled to town during the attack but I was left behind,” she said. “I was not afraid because I am blind and you cannot fear what you don’t see! But I was very thirsty because there was no water during that period.”

Other people with disabilities who stayed behind said they only managed to survive because they hid from attackers in time.

A 60-year-old man with a physical disability said he decided to stay behind when government soldiers attacked his village in Mayendit county on the very day that the famine was declared in the area:

We were still sleeping when we heard the gunshots. I took my cane and stood up to leave the house and run to a nearby riverbed. I hid there alone for a good 12 hours because I told the children to run ahead with their mother. I cannot move fast enough and did not want to slow them. From where I hid, I saw the soldiers loot the whole village and burn it to the ground.

In rarer occasions, soldiers or commanders protected people with disabilities and older people who had been left behind.

In late January 2017, soldiers spared the lives of a number of people with disabilities and older people who had been left behind when government forces captured Wau Shilluk, a settlement near Malakal that hosted about 20,000, mostly Shilluk, displaced people.

About 30 of them were taken to the Malakal site for displaced people by nongovernmental group workers a month later. Those interviewed shortly after their arrival said that government troops did not abuse them upon order from their commander, who also instructed his forces to bring them food and water daily for over a month.

An older woman with sensory and physical disabilities said that she had declined to run away when the soldiers arrived in Wau Shilluk:

I told my daughter to go and leave me here because I am blind and cannot walk. I was afraid of slowing down other people. If I die, it is no problem, I told my daughter. When the soldiers arrived, they found me in my hut and said ‘We are with the government, and if it is OK with you we will bring you to another home with other people like you,’ which they did. And then they brought us food and water every day until the aid workers brought me to the Malakal PoC.

Challenges Accessing Aid

Displaced people with disabilities and older people who have sought refuge in the remote bushes of Western Bahr el-Ghazal, Upper Nile, Jonglei, and the Equatorias or on islands in the Sudd, are more likely to encounter difficulties getting aid than those who found their way to the PoC sites inside UN bases.

A blind 70-year-old displaced man in the Sudd said that there are gaps in the aid coverage. “Life on the islands is hard,” he said. “Some organizations have registered older people, but I never got registered because they did not come to this particular island. There’s no health clinic either on the island. To get medical assistance, I must travel to another island or to the mainland.”

On dozens of other refuge islands scattered through the swamps, nestled in and around the areas where the famine has been declared, conditions can be extremely difficult for people with disabilities and older people without nearby relatives. An 80-year-old man with lower body paralysis on Mer island said that food was scarce. “Sometimes I eat, sometimes I don’t,” he said. “I can go on for five days without food. All I have is water. When I am thirsty, I have to crawl to the borehole. I push the water can in front of me, and then I need to ask a child to pump the well for me. It takes a very long time to get to the water.”

The situation is a little easier in the UN sites. Now hosting more than 210,000 civilians in and around six UN bases, the PoC sites allow for a more effective distribution of aid and better protection. However, even in these sites, people with disabilities and older people encounter challenges getting services.

Conditions differ depending on the service providers in each site. Water and sanitation facilities, for instance, are not equally accessible to people with disabilities and older people living in the camps. For the time being, only a few latrines in the Malakal PoC site have been adapted to the needs of people with physical disabilities, with more about to be built. In the Juba PoC sites, there are more accessible latrines but not in every quarter.

A 37-year-old man with a physical disability in Juba said that the accessible toilets are often too far away from the homes of people with disabilities. “The regular latrines are not OK for us because there are no seats or hand bars to help us defecate,” he said. “And the specialized latrines are not enough in the camp, so going from home to the latrine can take a very long time. All the zones of the camp should have their own latrine for people with disabilities.”

People with disabilities interviewed in the Juba and Malakal said that the few adapted latrines they had access to were frequently used by other people and children, who often urinated or defecated on the sides, making it difficult for those needing to crawl into the latrine.

The common showers are not easier to use either because the floor is too high in Juba or made of slippery tarpaulin in Malakal. A 30-year-old singer who moves around on a tricycle and lives in the Juba site, said that it was almost impossible for him to reach the showers:

The floor of the shower rooms is almost half a meter above the ground, so people like me find it very difficult to climb in there. I have to bring the water in a jerrycan and then lift it in there, and there I have to try and stand on my tricycle to get in. I often fall to the ground.

As a result of these difficulties, many people with disabilities interviewed said that they preferred to take their showers right outside of their homes at night.

In the camps, getting food can also be a challenge for people who struggle to stand in line during distributions or to carry their rations back home. They often must rely on relatives or neighbors. “After receiving my rations, I have to ask someone with a wheelbarrow to carry in exchange for some money or a cup of grain, because I can’t carry it myself,” a 42-year-old man with a physical disability said at the Juba PoC site.

Schools in the PoC sites are also not adapted for students with sensory or intellectual disabilities.

A 22-year-old man with a developmental disability and leg paralysis said he had numerous problems in his quest to get his primary school diploma in one of the Juba PoC sites:

I want to go to school and play football because in my heart I want to become a footballer so I can run and strengthen my legs. But when I go to school, the children are very aggressive toward me. When I move around, I fall sometimes and they laugh at me because my tongue is weak and I cannot speak well. If I report to the teachers, they don’t do anything and often they tell me to sit at the back of the class. So sometimes I decide not to go to school and my heart beats very fast because I feel sad.

People with disabilities and older people can also occasionally face stigma and abuse from family and the community. “We’ve encountered cases of relatives physically abusing people with disabilities, beating them or forcibly taking their food or other possessions from them,” an aid worker said. Such abuse raises protection concerns that are frequently difficult to address because of the abused person’s dependence on relatives or neighbors who may be the ones abusing them.

People with disabilities and older people living in the sites also need help to make a living. Given the insecurity that usually surrounds the camps, people with disabilities or older people are less likely than others to have the opportunity to cultivate, fetch wood, or trade outside of the sites. Such economic insecurity can lead to heightened depression and anxiety among vulnerable displaced people.

A single mother of five children whose leg was amputated after she was struck by a bullet during a government attack on the Bor camp in 2014, said that the poor living conditions in the camp greatly affect her morale:

Now, I am thinking too much. Not about my disability but about how I can support my children. It is too much and I sometimes think that it is better for me to die because no one is supporting us. The PoC is very hot, there is no water, no soap, the plastic sheet that make up the shelter are broken and I don’t know how I can support my children.

“People with special needs are often invisible, and their needs are not brought up to the surface,” a representative from HelpAge said in Juba. “Rarely do health organizations treat non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes or high blood pressure for instance. Likewise, few are preoccupied with the malnutrition of older persons or people with disabilities; the focus is on children and pregnant mothers.”