When students with disabilities enter Monroe High School, they often spend nearly a decade learning that their differences mean they will be educated separately from their peers who spend their days in mainstream classrooms.

But that all changed when classes started at Monroe High School northeast of Seattle, where administrators had set up a system that forced students to spend most of their time in general education classrooms, regardless of their needs.

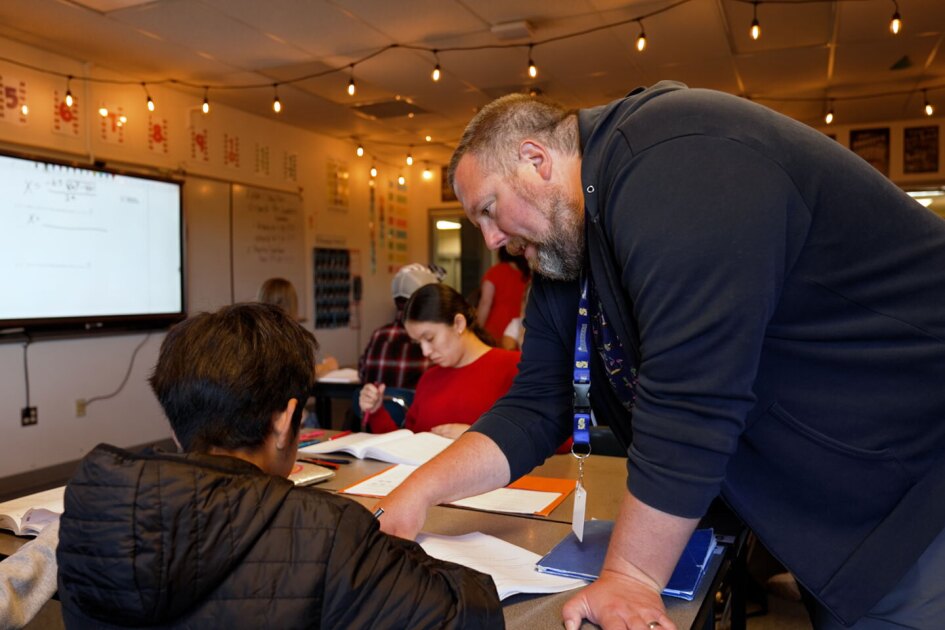

Rather than being pulled out of class for specially adapted instruction, students with disabilities most often receive the supports specified in their Individualized Education Program (IEP) or 504 plan (such as math lessons, extra help with emotional regulation or communication) in the regular classroom.

“Faculty members need to continue to learn, be prepared to be uncomfortable,” Principal Brett Wille said, “and understand that we are literally changing a system that was not designed for these outcomes and be excited to be part of the solution.”

Monroe is one of 16 schools in Washington state partnering with the University of Washington’s Harring Center for Inclusive Education, with the goal of demonstrating that when schools are intentionally created to consider the needs of students with disabilities, all students benefit.

Participating schools receive mentoring and professional development from Harring Center staff, who, in addition to other teachers and school principals, frequently observe the schools’ work and provide feedback on what’s going well and what needs improvement.

The partnership, made possible by a grant from the state government, aims to help achieve more inclusive practices in the state, particularly reaching a standard where students with disabilities spend at least 80 percent of their time in general education classrooms.

This goal is driven by federal policy that requires students to be educated in the “least restrictive environment” appropriate. Nationwide, two-thirds of students with disabilities will meet this goal in fall 2022, up from 60.5% in 2010 and less than half in 2000, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

The partnership is expected to expand in the fall to include 22 schools, spanning elementary through high school, each level presenting its own unique challenges and opportunities.

For Monroe High School, Wille said the biggest challenge — and opportunity — is combating the stigma that students with disabilities can feel because they have needed special assistance their entire academic lives.

“It takes some time for kids who have spent years and years in the system, isolated and excluded, to believe in themselves again,” Wille says. “And yet we’re saying, ‘No, we’re going to cut it off here.'”

A 2022 study of Indiana students published in the Journal of Special Education found that students with disabilities tend to do better academically when they spend significantly more time in mainstream classrooms, in large part because they receive more rigorous coursework in mainstream classrooms.

Researchers have also found that including students with disabilities in general education classes helps students without disabilities learn to respect and help others. Several studies over the years that have looked at these more inclusive practices have found neutral or positive effects on all students’ performance in core subjects like math and reading.

Monroe has additional staff in classrooms ready to assist students with special needs, so students are pulled out of general education classrooms less frequently. This year, the school also introduced an integrated basketball team, where students with and without disabilities play on the same team.

Monroe High School has made great strides in recent years, but Wille said there is a need to go further.

But Wille is confident it will happen, pointing out that there is anecdotal evidence that students of different abilities and backgrounds have gained important social skills like empathy and respect through learning in a diverse environment. Students with disabilities in particular have “regained their dignity,” Wille said, and become more self-confident.

“It starts with high standards for what we want all students to learn,” Wille said, “and then we figure out how to get there with all students, not separating, ranking or categorizing students and excluding them from the experiences that all students should have.”