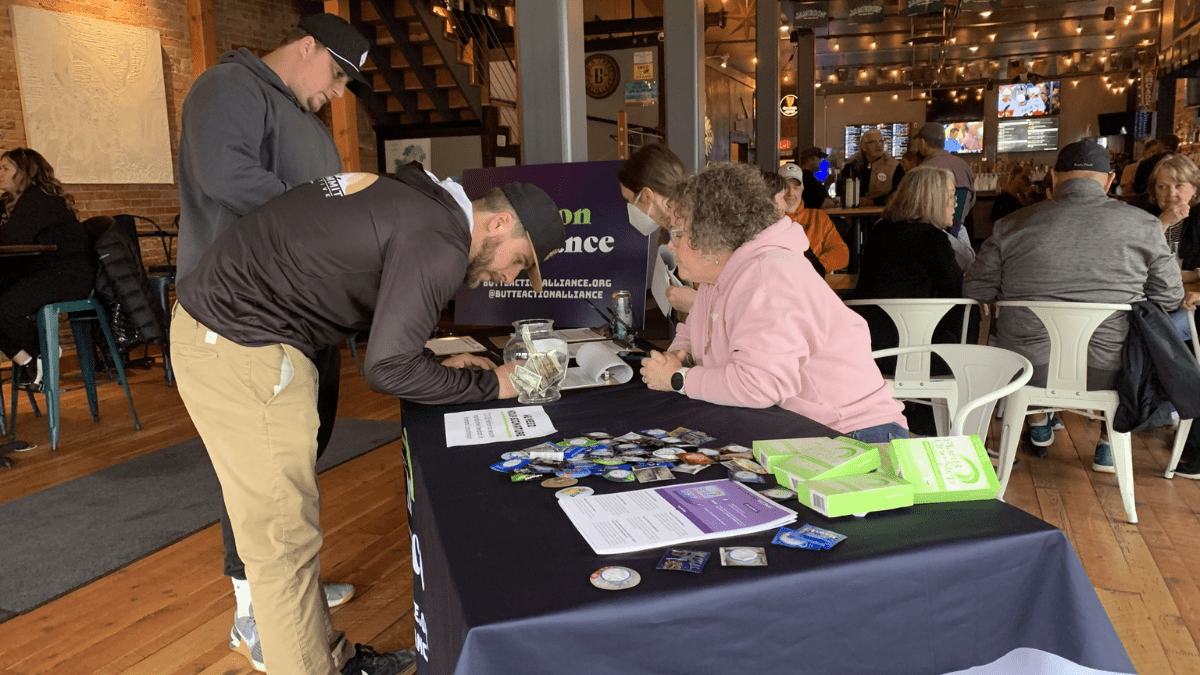

Gwendolyn Chilcote tried to make it hard for patrons entering a bar in uptown Butte to miss her. On a Tuesday in mid-May, she wore a pink sweatshirt, smiled brightly and didn’t hesitate to make eye contact. Before they passed her table, she used one question to snag as many people as possible.

“Have you signed the petition for reproductive rights yet?”

Two of the incoming pub-goers were bearded men in hoodies and baseball hats who looked to be in their early 30s. They hadn’t signed the petition supporting Constitutional Initiative-128 and doubled back to hear more.

Chilcote, who volunteers with the local reproductive rights group Butte Action Alliance, gave them her intentionally crafted spiel. Signing the petition supports putting CI-128 on the ballot, she said, and if the campaign gathers more than 60,000 signatures, voters in November will be able to choose whether to keep pregnancy decisions in Montana between a woman and her doctor.

The men, both registered voters, nodded and jotted down their names. Chilcote kept a close eye on their progress. One mistaken date or illegible address would make the signature worthless. When they walked away, she leaned back and briefly relaxed. Two down, thousands more to go.

The last week of May marked about eight weeks of CI-128’s signature-gathering campaign and about three weeks until the sponsoring group Montanans Securing Reproductive Rights, or MSRR, must submit verified signatures to local election administrators. If that effort is successful, Montanans will have the chance to vote “yes” or “no” on the explicit constitutional abortion protection in the fall.

Supporters and opponents of CI-128 acknowledge that getting the initiative on the ballot is not a sure thing. A multi-month court battle between MSRR and Montana’s Republican Attorney General Austin Knudsen pushed back signature gathering by several weeks, much to the frustration of CI-128 advocates and the relief of anti-abortion groups.

And, even as MSRR touts a wave of volunteer interest, the group’s strategy for gathering signatures has been intentionally cautious. Organizers have avoided holding large public events or publicly posting the addresses of campaign offices out of fear of harassment and violence from anti-abortion advocates. Instead, MSRR has opted to send volunteers and paid staff from the firm Landslide Political out to pound the pavement, knock on doors and circulate clipboards among their friends and family.

MSRR declined to say how many signatures it has collected so far. A spokesperson for the Montana Secretary of State’s Office said that, as of May 29, MSRR has not submitted any of the 60,359 required signatures.

Opponents are organizing, too. In recent weeks, a political committee called the Montana Life Defense Fund has ramped up alternate messaging about CI-128, claiming it would usher in an era of limitless abortion and lead to a series of negative consequences. As the June 21 deadline approaches, the group is training its own volunteers to deter petitioners and, when sheets of signatures are submitted, to weed out ineligible names turned in to election officials.

In this image obtained by MTFP, a volunteer for Montanans Securing Reproductive Rights, second from left, speaks with an officer from the Helena Police Department on May 13, 2024, while being observed by Patrick Webb, left, and Derek Oestreicher, second from right, organizers with Montana Life Defense Fund.

In this image obtained by MTFP, a volunteer for Montanans Securing Reproductive Rights, second from left, speaks with an officer from the Helena Police Department on May 13, 2024, while being observed by Patrick Webb, left, and Derek Oestreicher, second from right, organizers with Montana Life Defense Fund.

The tension around CI-128 underscores Montana’s evolving landscape for abortion rights. Access remains legal and mostly unencumbered in the state while a plethora of Republican-backed prohibitions are blocked in court. Supporters of CI-128 say enshrining protections in the state Constitution is essential given those recent efforts and since the end of Roe v. Wade. For opponents, CI-128 represents an existential threat to the anti-abortion cause in Montana — a bulwark that, once built, would be exceedingly difficult to overcome.

For voters, the initiative represents a historic opportunity to weigh in on the question of legal abortion. Chilcote said she’s met plenty of people who are excited to sign the petition, while others haven’t heard about it at all and don’t understand why it’s necessary when abortion is already permitted in Montana.

“I wonder if it’s because abortion hasn’t been outlawed yet so people don’t realize it’s in danger,” she said. “And what I’m telling people is, ‘Not yet.’”

ORGANIZED OPPOSITION

A few days before Chilcote set up her signature-gathering station in a Butte bar, the Montana Life Defense Fund scheduled a volunteer training for anyone interested in preventing CI-128 from advancing to the ballot.

The group’s leadership includes Jeff Laszloffy, the president of the conservative Christian policy nonprofit the Montana Family Foundation, and two lobbyists. Laszloffy didn’t respond to Montana Free Press’ requests to attend the ongoing training. But, in a mid-May episode of the organization’s podcast, organizers Patrick Webb and Derek Oestreicher laid out the aims of the opposition campaign: Spread the message that CI-128 is vague and could have serious downstream effects, and, ultimately, recruit volunteers willing to help curb the initiative’s progress.

“We have been operating to do everything we can to prevent this from gaining access to the ballot,” Webb said in the podcast.

One of the group’s most visible strategies has been videotaping CI-128 volunteers working in public places — a tactic that requires audibly announcing that an observer is recording, per Montana law. So far, Webb and Oestreicher said, they’ve found the strategy successfully disrupts signature gathering by “shining a light” on the process.

“Them not getting out and actually signing up every person that comes by, because they are actually trying to walk away from our people or get away from the camera, prevents them from getting signatures,” Webb said. “When we multiply this across multiple people doing this in each county where they’re at, we can stop them from getting this on the ballot. We can stop CI-128.”

Montana Life Defense Fund used this strategy at least once in Helena in early May. A CI-128 volunteer on the downtown strip of Last Chance Gulch called the police after Webb began videotaping her, according to photos and a video reviewed by MTFP. The Helena Police Department later told MTFP that responding officers hadn’t identified any illegal activity and that people are permitted to videotape in a public place.

In an emailed comment, Laszloffy said the event was “nothing newsworthy” and that Webb was within his right to videotape signature gathering on public property.

“No harassment, no confrontation. Patrick was simply videotaping the process,” Laszloffy said.

State law prohibits physically preventing or physically intimidating signature gathering for statewide ballot issues. MSRR has not filed a lawsuit about the videotaping incidents or any other interactions with its volunteers or staff but has said the campaign is “monitoring the situation closely.”

“Them not getting out and actually signing up every person that comes by, because they are actually trying to walk away from our people or get away from the camera, prevents them from getting signatures.”

Patrick Webb, Montana Life Defense Fund organizer

“The opposition knows that Montanans support reproductive rights so they are resorting to these tactics to silence voters,” said Kiersten Iwai, the executive director of Forward Montana, one of MSRR’s member groups, in a written statement. “We will remain focused on the task at hand — collecting signatures so that voters can make their voice heard.”

Several opponents of CI-128 have also filed complaints with the Commissioner of Political Practices against the MSRR campaign alleging violations in signature gathering. Some of the complainants describe watching CI-128 organizers for hours in Billings, Bozeman and near Stevensville, quizzing them about the initiative’s implications, filming them at various locations and standing close enough to hear their interactions with voters.

In letters to the complainants and the MSRR campaign, Commissioner of Political Practices Chris Gallus said that none of the allegations — including that CI-128 petitioners left clipboards unattended and failed to ask signers if they were registered to vote — fall under his jurisdiction until after petitions are submitted.

A spokesperson for MSRR called the complaints “baseless” and an apparently coordinated effort by opponents of CI-128.

“All of our signature gatherers go through thorough training. Despite the extreme opposition’s desperate tactics, our signature gatherers are doing an excellent job focusing on the qualification of CI-128,” said campaign spokesperson Ashley All.

Laszloffy did not respond to MTFP’s questions about whether his group was training volunteers to submit complaints to the Commissioner of Political Practices.

Kelly Hall, the executive director of The Fairness Project, one of the national groups backing the CI-128 campaign, said the opposition tactics playing out in Montana are “nearly identical” to those happening in other states considering reproductive rights initiatives, such as Arizona and Missouri. She cast the “decline to sign” movements as evidence that, above all, opponents fear these measures going before voters.

“They are a demonstration, typically, of the fact that even these activists know that the electorate is not with them on this issue. That the most efficient way that they can get their policy preference to be the law of the land is to prevent voters from getting to express their will at the ballot box,” Hall said.

In the May podcast episode, Webb and Oestreicher stressed that opponents of CI-128 can volunteer in any capacity that suits them. Not everyone has to confront signature gatherers on the street, they said. Even making baked goods for a “signature verification party” helps propel the movement forward. The most important thing, they said, was to raise a grassroots campaign that can challenge the proponents.

“The next six weeks are paramount. If you can spare, you know, a couple hours even, every week for the next six weeks. Let us know. Get in touch,” Oestreicher said. “We can outperform them. Okay? We can do it.”

A CAUTIOUS APPROACH

Opponents of CI-128 were nowhere to be seen near the Beartracks Bridge in Missoula in late May, where Lillian Thomas was stationed with an MSRR clipboard. Even still, she said, new supporters were proving hard to come by compared to when she began volunteering for the campaign a few weeks earlier.

The weather had been intermittently cold and rainy, she said, putting a damper on foot traffic. On the other hand, many passersby spotted her clipboard pasted with MSRR’s teal blue logo and told her they’d already added their names to the petition. Thomas takes that as a good omen — that the group has managed to reach much of Missoula’s pool of registered voters — but wonders about where she can find more supporters who haven’t signed.

Lillian Thomas stands on the Beartracks Bridge in Missoula in late May to collect signatures for CI-128, the constitutional abortion rights initiative. Credit: Mara Silvers / MTFP

Lillian Thomas stands on the Beartracks Bridge in Missoula in late May to collect signatures for CI-128, the constitutional abortion rights initiative. Credit: Mara Silvers / MTFP

In a little under an hour, Thomas and another MSRR volunteer tallied nine new signatures and had conversations with many more supporters who had already signed. Three people firmly declined to join the petition, with two explicitly citing their opposition to abortion.

Thomas said that over several weeks of volunteering, interactions with opponents have been rare and enthusiastic support common. She recalled one man who saw her clipboard while dining outside at a downtown Missoula restaurant. He briefly abandoned his table to run after Thomas so he could sign the petition and then asked her to come back to the restaurant so his wife could, too.

Earlier that day, other volunteers swapped signature-gathering stories while dropping off petitions at the Missoula CI-128 office. Some had gone door-to-door in Missoula neighborhoods or staked out a corner at weekend farmers markets in Kalispell and Whitefish. Their positive interactions far outnumbered any confrontations with opponents of the initiative, they said. In the rare case someone raised their voice or started to speak against abortion, most volunteers opted to politely disengage and move on to other potential supporters.

Still, the prospect of disruption, harassment and threats of violence from people who oppose abortion hangs over many aspects of the CI-128 campaign. Some volunteers in more conservative pockets of the state aren’t gathering signatures at all for fear of adversarial interactions but, instead, are speaking to their friends and families about the initiative’s aims. MSRR has held door-knocking events in Butte and plans to do more in Helena and Billings in the coming weeks. But the campaign is avoiding holding public events or establishing regular signature-gathering hours in the same place, a strategy meant to prevent bad actors from threatening staff and volunteers.

Hall, with The Fairness Project, said methods for canvassing efforts vary widely by state. But she added that many campaigns the group has supported have benefitted from volunteer signature gatherers.

“The overwhelming momentum and enthusiasm from volunteers to go out with signatures and collect in their communities, under their own volition, where they know people, where they frequent, where they think there are going to be people for them to communicate with — those volunteers are really the lifeblood of any of these campaigns,” Hall said.

In Missoula and Butte, volunteers and signatories to CI-128 repeatedly asked how many signatures had been gathered across the state and in different towns. Organizers, in turn, declined to give specifics, only sharing that the campaign was “on track” to meet its local and statewide goals.

All, the MSRR spokesperson, directly attributed that tight-lipped posture to the tense political environment.

“Due to the extreme opposition’s harassment of our volunteers and staff and their efforts to deceive and obstruct voters who want to sign the CI-128 petition, we will not be sharing signature numbers or counts by location,” All said. “We take safety very seriously. We will not do anything that might encourage anti-abortion extremists to further harass or intimidate our signature gatherers.”

In Butte, several signatories told Chilcote that they had come to the pub solely to sign CI-128 upon hearing about the event from friends or on Butte Action Alliance’s social media. Others said they had been trying to sign for several weeks and wished that access was more straightforward.

Thomas, the volunteer from Missoula, has also been frustrated at times by the campaign’s tactic of seeking signatures one by one, rather than holding well-publicized events to encourage supporters to come to them en masse. She said she’s heard similar sentiments from people she meets while canvassing.

“There have been multiple people who have said that kind of thing. Like, ‘Oh, I know my friend really wants to find this. How can they find you? How can they find you?’” Thomas said.

At the same time, Thomas said she understands how the specter of aggression and threats from the opposition creates a chilling effect.

“Obviously, you don’t want to set yourself up to be targeted,” she said. “What a barrier.”

latest stories

State hospital shuffles top leadership, again

Roughly six months before its goal of applying for federal certification of the Montana State Hospital, the state health department is again juggling turnover in key leadership positions at the state’s only public adult psychiatric facility.

Judge denies request to block education savings account law

A state judge in Helena has denied a request by Disability Rights Montana and the Montana Quality Education Coalition to block a law establishing savings accounts for students with special needs until ongoing litigation is resolved.

Why it takes a crisis to trigger funding for Montana’s largest irrigation project

The rivets were still popping from the seams of the St. Mary siphon when Jennifer Patrick started crunching the numbers for repairing the century-old system that 18,000 residents of Montana’s Hi-Line depend on for water. It would take 3,600 feet of pipe so big men can walk through it without bumping their heads. They would need a new steel bridge across the St. Mary River and enough earth-moving equipment to restore a river channel completely buried beneath rocky soil eroded from the hillside where the siphon blew. They were short of one thing money couldn’t…