By the time Gina Hemphill approached Rafer Johnson with the blazing Olympic torch at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on that unforgettable Saturday night, July 28, 1984, a lot had already happened.

The International Olympic Committee was struggling. The murder of an Israeli athlete at the 1972 Munich Games was still fresh in many people’s minds. Huge budget overruns and the image of a large, unfinished construction crane that had been hanging above the main stadium throughout the 1976 Montreal Games had further tarnished the Olympics’ image. And then, at the behest of President Jimmy Carter, the United States boycotted the 1980 Moscow Games in protest of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

So the race to host the 1984 Olympics was decided to be between Los Angeles and Tehran, a choice the IOC could not afford to make.

Despite a campaign spearheaded by civic activist John Argue and Mayor Tom Bradley, Los Angeles resisted the idea for several years. It would cause too much traffic, disrupt daily life too much, and probably be too much of a burden for the vast majority of taxpayers who couldn’t care less about shot putters or people shooting arrows at targets.

In the end, Argue, Bradley and the Los Angeles Games’ chairman, prominent local lawyer Paul Ziffren, took a gamble and hired Peter Ueberroth, a travel executive from the San Fernando Valley, to run the operation. Ueberroth brought in a partner, a local lawyer named Harry Usher, and the next four years were unprecedented for the city, even including Los Angeles’ first Olympic Games in 1932.

Sponsors needed to be found. Locations for all the events needed to be identified. Volunteers needed to be recruited. A roster of highly skilled additional officials needed to be persuaded to sign on, often with barely any salaries until close to the Olympics. An organizational chart was needed that would make IBM proud. Most importantly, television stations needed to be grabbed by the collar and convinced that they needed to pay an upfront fee just to have the rights to broadcast the Olympics in their airspace. When Ueberroth took over the Olympic office, all he was given was a set of keys and a rent bill.

It was a mountain taller than Everest to summit, but a few years later, when Jesse Owens’ granddaughter Hemphill reached Mount Johnson, there were only 32 significant steps remaining to the summit — 32 steps that would sanction all the work and justify all the effort.

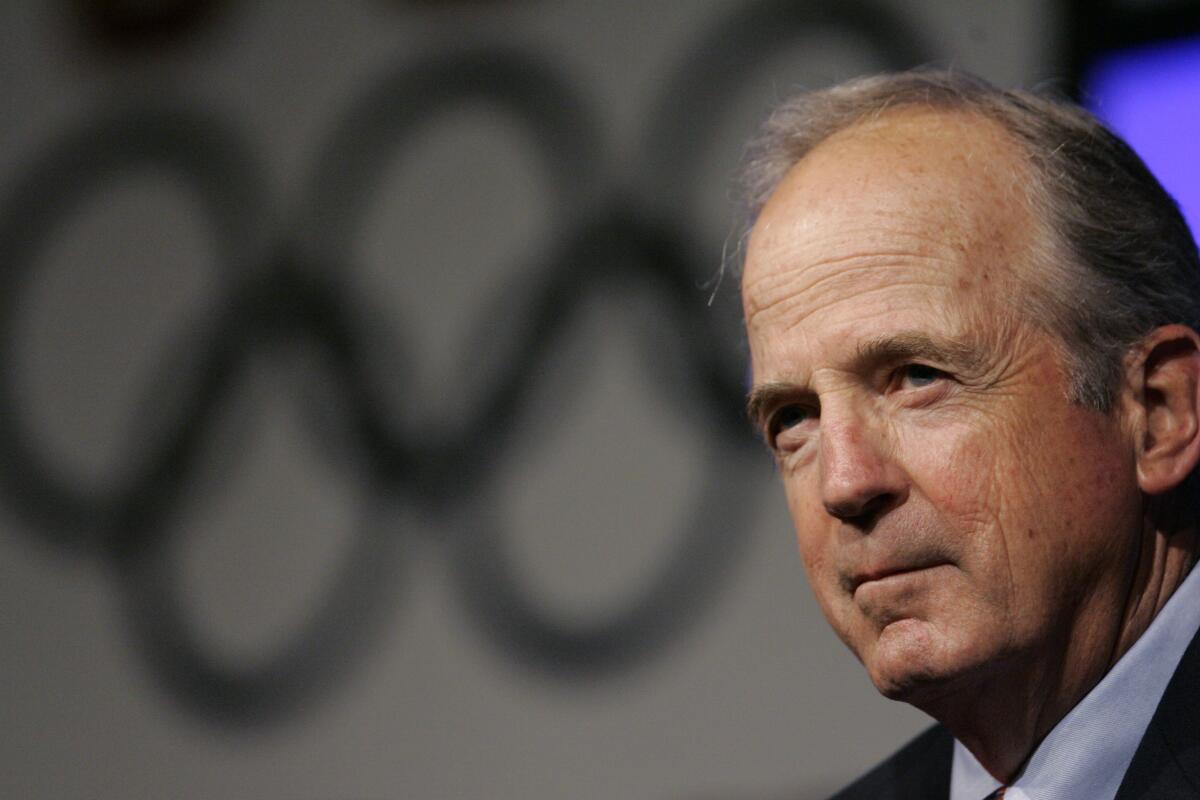

Peter Ueberroth, architect of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games (2008).

(M. Spencer Green/The Associated Press)

The opening ceremony drew 92,515 people to the Coliseum, all of whom felt lucky just to be there, watched the Rocket Man fly through the sky, and saw 1,000 volunteers holding balloons that read “Welcome” on the Coliseum floor. Soon, 84 grand pianos were playing “Rhapsody in Blue” and President Ronald Reagan officially opened the Olympics.

All that was left was the symbolic lighting of the torch, the moment when the host city announced that it was time for the lights to be turned on for all to enter and enjoy. It was such a joyous moment.

Jim Murray, a Times sports columnist who later won a Pulitzer Prize, put it in a way few others could: “The Opening Ceremony is not the beginning of the Olympics, it’s the pinnacle. It makes an Olympic statement. It’s a valentine to tomorrow. Tomorrow is OK. Tomorrow is in good hands.”

Forty years ago, the City of Angels danced, celebrated and, for at least a few weeks, felt like the best place in the world.

The weather was near perfect. People who had been indifferent about the whole thing ended up desperately trying to get tickets to whatever event was happening. Ueberroth and his team came up with ways to reduce traffic congestion, including running large numbers of buses and shift reassignments. Thousands of people, fearing the worst, left town.

So the transportation companies cooperated and so did the players.

Carl Lewis was a big deal because many were hoping to repeat Owens’ four gold medal feat in Berlin in 1936. And he did: Lewis won the 100 and 200 meters, anchored the winning 400 relay, and competed in the long jump.

Evelyn Ashford and Valerie Briscoe-Hooks won gold medals in the women’s sprints.

The IOC has never allowed women to run their own marathon. But in Los Angeles, 5-foot-2, 100-pound Joan Benoit from Maine strode into the Coliseum for the final lap and a jubilant celebration. The jubilation was tempered when Gabriela Andersen-Scies, a ski instructor from Idaho running for her native Switzerland, entered the Coliseum with suspected heat stroke. Writhing in pain, she managed to complete the final lap, walking most of the distance, but no one touched her and disqualified her. She crossed the line and doctors carried her out on a stretcher, wrapped her in ice. She recovered and ran another race a few weeks later.

Rowdy Gaines and Tracy Caulkins were the stars of the swimming events, and Greg Louganis won the diving event by a large margin, as most expected.

With the Soviets boycotting in retaliation, the United States dominated both basketball tournaments, with Michael Jordan’s men’s team, coached by Bobby Knight, and Cheryl Miller/Kim Mulkey’s women’s team, coached by Pat Summitt, winning gold medals.

In the men’s soccer event, tickets for the third-place playoffs were sold out, surprising even the organizers. Attendance at the Rose Bowl for the bronze medal match between Yugoslavia and Italy was 100,374. A few more, 101,799, attended the gold medal match between France and Brazil. The international soccer world began to think that maybe a World Cup in the United States and Los Angeles would work after all.

Mary Lou Retton became famous for her joyous gymnastics routines, and the underrated U.S. men’s team, led by Bert Conner, Mitch Gaylord, Peter Widmer and Tim Doggett, stunned the sports world with a late-night team victory that few expected.

American gymnast Mary Lou Retton celebrates after winning the gold medal in the women’s individual all-around at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

(Tony Bernard/Los Angeles Times)

And then, on the final Friday night of the Olympics, there was the women’s 3,000 meters, with the Coliseum crowd hoping to see home-grown star Mary Decker in action and to see what it would be like to see a South African teenager running barefoot in the same race for England. Weighing just 100 pounds, 18 years old and too shy to defend herself when needed, Zola Budd was about to become part of the biggest story of the 1984 Olympics.

Midway through the race, Budd passed Decker for the lead. Decker was close to Budd and the two became briefly entangled. A few steps later, Budd’s left foot struck Decker’s thigh, causing Budd to lose his balance and go into Decker’s path. Decker appeared to step on Budd’s heel. Decker stumbled and, as he fell, lunged toward Budd, ripping Budd’s bib number from his back.

Decker was injured and writhing in pain in the infield. Budd saw Decker go down, turned around and kept going. Soon a chorus of boos erupted from the Coliseum crowd. He stayed near the front for a while, but then fell back, eventually finishing in seventh place.

Years later, Budd told a Times reporter that she knew she could have won a medal. She knew that the eventual winner, Marica Puka of Romania, was the strongest athlete in the event, but she was disappointed that she was overshadowed by the Decker-Budd frenzy. Budd said she was scared to stand on the medal podium and be booed.

Decker missed one Olympics during his prime due to injury and another because of the U.S. boycott in Moscow, and despite being one of the sport’s top distance runners, he never won an Olympic medal.

When Budd approached Decker in the Coliseum tunnel after the incident, Decker yelled at her to leave. Budd returned to her hotel in Los Angeles with her mother, only to be warned that death threats were being made. The next day, security drove her and her mother directly to Los Angeles International Airport and escorted them to the runway, where they boarded a plane to escape the Olympic nightmare and return home to South Africa.

A few months later, Ueberroth was a surefire nominee for Time magazine’s Person of the Year. He paid all expenses and made a net profit of $232.5 million from the Olympics, which still funds sports programs throughout Southern California today through the LA84 Foundation. One day, he heard that the magazine had come out and that he was on the cover. He decided to walk to a store near his home in Laguna Beach, where he knew there was a newspaper stand.

“I was unshaven and wearing some old clothes,” Ueberroth said, “and I walked in and there I was on the cover of Time magazine.”

Yuberoth picked up the stack of magazines and headed to the register, where the clerk looked confused. Sensing the clerk’s hesitation, Yuberoth told the clerk that he was the man on the cover. The clerk stared at the bearded, casually dressed customer, took a quick look at the magazine’s cover, which featured a man in a suit and tie, and then told Yuberoth that all the magazines had been reserved by other customers.

Mr. Ueberroth always chuckles when he tells this story: After all, the Man of the Year had no influence whatsoever over the clerk on duty.